Degradation Data Analysis

Given that products are more frequently being designed with higher reliability and developed in a shorter amount of time, it is often not possible to test new designs to failure under normal operating conditions. In some cases, it is possible to infer the reliability behavior of unfailed test samples with only the accumulated test time information and assumptions about the distribution. However, this generally leads to a great deal of uncertainty in the results. Another option in this situation is the use of degradation analysis. Degradation analysis involves the measurement of performance data that can be directly related to the presumed failure of the product in question. Many failure mechanisms can be directly linked to the degradation of part of the product, and degradation analysis allows the analyst to extrapolate to an assumed failure time based on the measurements of degradation over time.

In some cases, it is possible to either directly measure the degradation of a physical characteristic over time, as with the wear of brake pads or with the propagation of crack size or the degradation of a performance characteristic over time such as the voltage of a battery or the luminous flux of an LED bulb. These cases belong to the Non-Destructive Degradation Analysis category. In other cases, direct measurement of degradation might not be possible without invasive or destructive measurement techniques that would directly affect the subsequent performance of the product and therefore only one degradation measurement is possible. Examples are the measurement of corrosion in a chemical container or the strength measurement of an adhesive bond. These cases belong to the Destructive Degradation Analysis Category. In either case, however, it is necessary to be able to define a level of degradation or performance at which a failure is said to have occurred.

With this failure level defined, it is a relatively simple matter to use basic mathematical models to extrapolate the measurements over time to the point where the failure is said to occur. Once these have been determined, it is merely a matter of analyzing the extrapolated failure times in the same manner as conventional time-to-failure data.

Non-Destructive Degradation Analysis

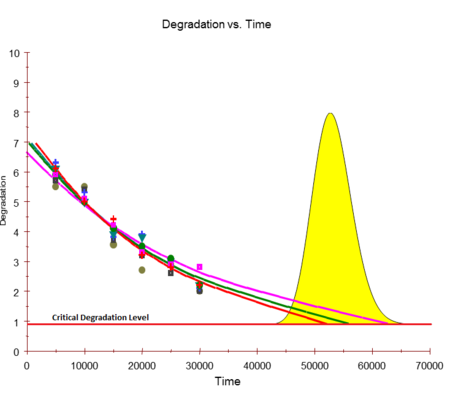

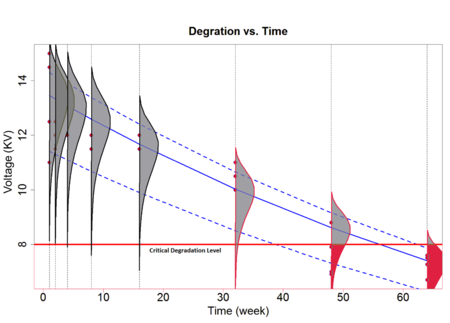

The Non-Destructive Degradation Analysis applies to cases where multiple degradation measurements over time can be obtained for each sample in the test. Given a defined level of failure (or the degradation level that would constitute a failure), basic mathematical models are used to extrapolate the degradation measurements over time of each sample to the point in time where the failure will occur. Once these extrapolated failure times are obtained, it is merely a matter of analyzing the extrapolated failure times in the same manner as conventional time-to-failure data. As with conventional life data analysis, the amount of certainty in the results is directly related to the number of samples being tested. The following figure combines the steps of the analysis by showing the extrapolation of the degradation measurements to a failure time and the subsequent distribution analysis of these failure times.

Once the degradation information has been recorded, the next task is to extrapolate the measurements to the defined failure level in order to estimate the failure time. Weibull++ allows the user to perform such extrapolation using a linear, exponential, power or logarithmic model. These models have the following forms:

- Linear: [math]\displaystyle{ y=a\cdot x+b \! }[/math]

- Exponential: [math]\displaystyle{ y=b\cdot {{e}^{a\cdot x}}\! }[/math]

- Power: [math]\displaystyle{ y=b\cdot {{x}^{a}} \! }[/math]

- Logarithmic: [math]\displaystyle{ y=a\cdot ln(x)+b \! }[/math]

- Gompertz: [math]\displaystyle{ y=a\cdot {{b}^{{{c}^{x}}}} \! }[/math]

- Lloyd-Lipow: [math]\displaystyle{ y=a-\frac{b}{x} \! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math] represents the performance, [math]\displaystyle{ x\,\! }[/math] represents time, and [math]\displaystyle{ a,\,\! }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ b\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ c\,\! }[/math] are model parameters to be solved for.

Once the model parameters [math]\displaystyle{ {{a}_{i}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{b}_{i}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{c}_{i}}\,\! }[/math] are estimated for each sample [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math], a time, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{i}}\,\! }[/math], can be extrapolated, which corresponds to the defined level of failure [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math]. The computed [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{i}}\,\! }[/math] values can now be used as our times-to-failure for subsequent life data analysis. As with any sort of extrapolation, one must be careful not to extrapolate too far beyond the actual range of data in order to avoid large inaccuracies (modeling errors).

Example

Crack Propagation Example (Point Estimation)

Five turbine blades are tested for crack propagation. The test units are cyclically stressed and inspected every 100,000 cycles for crack length. Failure is defined as a crack of length 30mm or greater. The following table shows the test results for the five units at each cycle:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{matrix} Cycles (x1000) & Unit A (mm)& Unit B (mm) & Unit C (mm) & Unit D (mm)& Unit E (mm) \\ 100 & 15 & 10 & 17 & 12 & 10 \\ 200 & 20& 15 & 25 & 16 & 15 \\ 300 & 22 & 20 &26 & 17 & 20 \\ 400 & 26 &25 & 27 & 20 & 26 \\ 500 & 29 & 30 & 33 &26 & 33 \\ \end{matrix}\,\! }[/math]

Use the exponential degradation model to extrapolate the times-to-failure data.

Solution

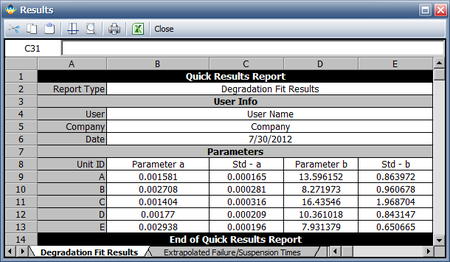

The first step is to solve the equation [math]\displaystyle{ y=b\cdot {{e}^{a\cdot x}}\,\! }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ a\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b\,\! }[/math] for each of the test units. Using regression analysis, the values for each of the test units are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{matrix} {} & a & b \\ Unit A & 0.00158 & 13.596 \\ Unit B & 0.00271 & 8.272 \\ Unit C & 0.00140 & 16.435 \\ Unit D & 0.00177 & 10.361 \\ Unit E & 0.00294 & 7.931 \\ \end{matrix}\,\! }[/math]

Substituted the values into the underlying exponential model, solved for [math]\displaystyle{ x\,\! }[/math] or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ x=\frac{\text{ln}(y)-\text{ln}(b)}{a}\,\! }[/math]

Using the values of [math]\displaystyle{ a\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b\,\! }[/math], with [math]\displaystyle{ y=30\,\! }[/math], the resulting time at which the crack length reaches 30mm can then found for each sample:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{matrix} {} & Cycles-to-Failure \\ Unit A & \text{500,622} \\ Unit B & \text{475,739} \\ Unit C & \text{428,739} \\ Unit D & \text{600,810} \\ Unit E & \text{452,832} \\ \end{matrix}\,\! }[/math]

These times-to-failure can now be analyzed using traditional life data analysis to obtain metrics such as the probability of failure, B10 life, mean life, etc. This analysis can be automatically performed in the Weibull++ degradation analysis folio.

More degradation analysis examples are available! See also:

![]() Degradation Analysis or

Degradation Analysis or ![]() Watch the video...

Watch the video...

Using Extrapolated Intervals

The parameters in a degradation model are estimated using available degradation data. If the data is large, the uncertainty of the estimated parameters will be small. Otherwise, the uncertainty will be large. Since the failure time for a test unit is predicted based on the estimated model, we sometimes would like to see how the parameter uncertainty affects the failure time prediction. Let’s use the exponential model as an example. Assume the critical degradation value is [math]\displaystyle{ {{y}_{crit}}\,\! }[/math]. The predicted failure time will be:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{x}=\frac{\ln ({{y}_{crit}})-\ln (\hat{b})}{{\hat{a}}}\,\! }[/math]

The variance of the predicted failure time will be:

- [math]\displaystyle{ Var(\hat{x})={{\left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial a} \right)}^{2}}Var(\hat{a})+{{\left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial b} \right)}^{2}}Var(\hat{b})+2\left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial a} \right)\left( \frac{\partial x}{\partial b} \right)Cov(\hat{a},\hat{b})\,\! }[/math]

The variance and covariance of the model parameters are calculated from using Least Squares Estimation. The details of the calculation are not given here.

The 2-sided upper and lower bounds for the predicted failure time, with a confidence level of [math]\displaystyle{ 1-\alpha \,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{U}}=\hat{x}+{{K}_{1-\alpha /2}}\sqrt{Var(\hat{x})}\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{L}}=\hat{x}-{{K}_{1-\alpha /2}}\sqrt{Var(\hat{x})}\,\! }[/math]

In Weibull++, the default confidence level is 90%.

Example

Crack Propagation Example (Extrapolated Intervals)

Using the same data set from the previous example, predict the interval failure times for the turbine blades.

Solution

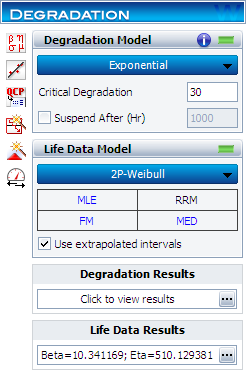

In the Weibull++ degradation analysis folio, select the Use extrapolated intervals check box, as shown next.

Use the exponential degradation model for the degradation analysis, and the Weibull distribution parameters with MLE for the life data analysis. The following report shows the estimated degradation model parameters.

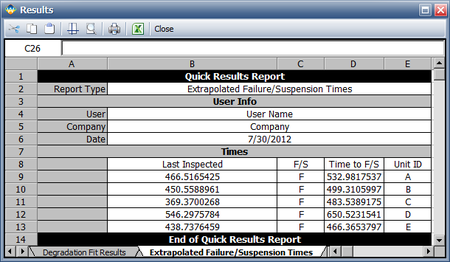

The following report shows the extrapolated failure time intervals.

Destructive Degradation Analysis

The Destructive Degradation Analysis applies to cases where the sample has to be destroyed in order to obtain a degradation measurement. As a result, degradation measurements for multiple samples are required at different points in time. The analysis performed is very similar to the Accelerated Life Testing Analysis (ALTA). In this case, the “stress” used in ALTA becomes time while the random variable instead of time-to-failure becomes the degradation measurement. . Given a defined level of failure (or the degradation level that would constitute a failure), the probability that the degradation measurement will be beyond that level at a given time can be obtained. The following plot shows the relationship between the distribution of the degradation measurement and time. The red shaded area of the last two pdfs represents the probability that the degradation measurement will be less than the critical degradation level at the corresponding times.