Life Distributions

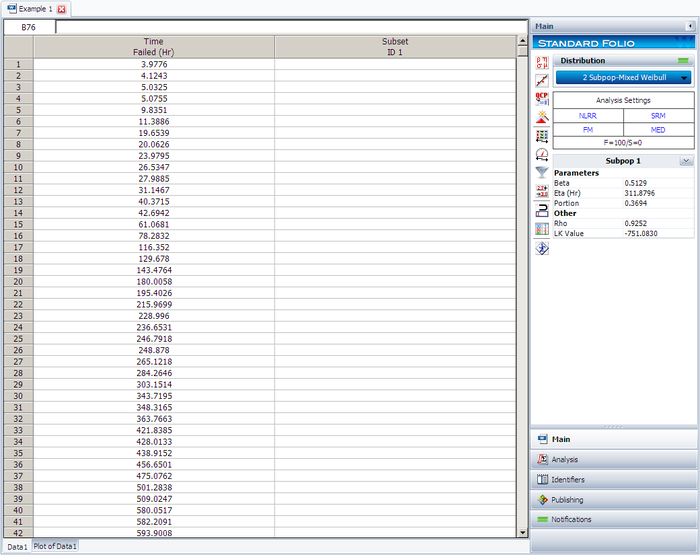

We use the term Life Distributions to describe the collection of statistical probability distributions that we use in Reliability Engineering and Life Data Analysis.

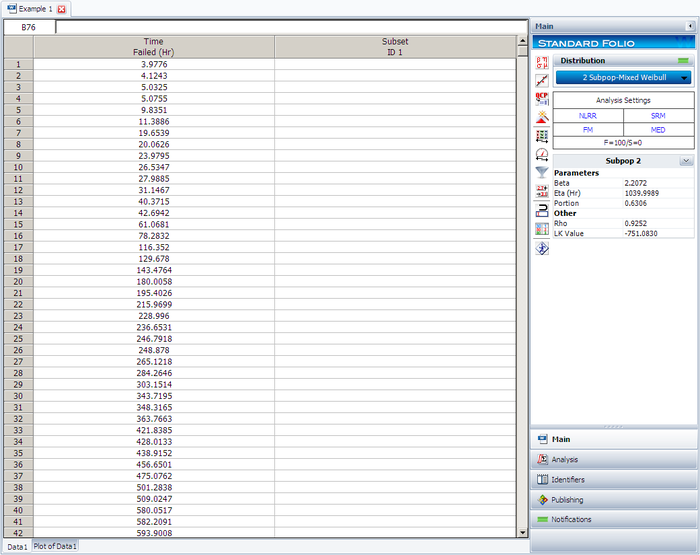

Life Distributions

A statistical distribution is fully described by its pdf (or probability density function). In the previous sections, we used the definition of the pdf to show how all other functions most commonly used in reliability engineering and life data analysis can be derived; namely, the reliability function, failure rate function, mean time function and median life function, etc. All of these can be determined directly from the pdf definition, or f(t). Different distributions exist, such as the normal, exponential, etc., and each one of them has a predefined form of f(t). These distribution definitions can be found in many references. In fact, entire texts have been dedicated to defining families of statistical distributions. These distributions were formulated by statisticians, mathematicians and engineers to mathematically model or represent certain behavior. For example, the Weibull distribution was formulated by Walloddi Weibull, and thus it bears his name. Some distributions tend to better represent life data and are commonly called lifetime distributions. One of the simplest and most commonly used distributions (and often erroneously overused due to its simplicity) is the exponential distribution. The pdf of the exponential distribution is mathematically defined as:

- f(t) = λe − λt

In this definition, note that t is our random variable, which represents time, and the Greek letter λ (lambda) represents what is commonly referred to as the parameter of the distribution. Depending on the value of λ, f(t) will be scaled differently. For any distribution, the parameter or parameters of the distribution are estimated from the data. For example, the well-known normal (or Gaussian) distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=\frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi }}{e}^{-\frac{1}{2}(\frac{t-\mu}{\sigma})^2} }[/math]

μ, the mean, and σ, the standard deviation, are its parameters. Both of these parameters are estimated from the data (i.e., the mean and standard deviation of the data). Once these parameters have been estimated, our function f(t) is fully defined and we can obtain any value for f(t) given any value of t.

Given the mathematical representation of a distribution, we can also derive all of the functions needed for life data analysis, which again will depend only on the value of t after the value of the distribution parameter or parameters have been estimated from data. For example, we know that the exponential distribution pdf is given by:

- f(t) = λe − λt

Thus, the exponential reliability function can be derived as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} R(t)= & 1-\int_{0}^{t}\lambda {{e}^{-\lambda s}}ds \\ = & 1-[ 1-{{e}^{-\lambda \cdot t}}] \\ = & {{e}^{-\lambda \cdot t}} \\ \end{align} }[/math]

The exponential failure rate function is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \lambda (t) =& \frac{f(t)}{R(t)} \\ =& \frac{\lambda {e}^{-\lambda t}}{e^{-\lambda t}} \\ =& \lambda \end{align} }[/math]

The exponential mean-time-to-failure (MTTF) is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mu = & \int_{0}^{\infty} t\cdot f(t)dt \\ = & \int_{0}^{\infty}{t \cdot {\lambda} \cdot e^{-\lambda t}}dt \\ = & \frac{1}{\lambda } \end{align} }[/math]

This exact same methodology can be applied to any distribution given its pdf, with various degrees of difficulty depending on the complexity of f(t).

We use the term Life Distributions to describe the collection of statistical probability distributions that we use in Reliability Engineering and Life Data Analysis.

Life Distributions

A statistical distribution is fully described by its pdf (or probability density function). In the previous sections, we used the definition of the pdf to show how all other functions most commonly used in reliability engineering and life data analysis can be derived; namely, the reliability function, failure rate function, mean time function and median life function, etc. All of these can be determined directly from the pdf definition, or f(t). Different distributions exist, such as the normal, exponential, etc., and each one of them has a predefined form of f(t). These distribution definitions can be found in many references. In fact, entire texts have been dedicated to defining families of statistical distributions. These distributions were formulated by statisticians, mathematicians and engineers to mathematically model or represent certain behavior. For example, the Weibull distribution was formulated by Walloddi Weibull, and thus it bears his name. Some distributions tend to better represent life data and are commonly called lifetime distributions. One of the simplest and most commonly used distributions (and often erroneously overused due to its simplicity) is the exponential distribution. The pdf of the exponential distribution is mathematically defined as:

- f(t) = λe − λt

In this definition, note that t is our random variable, which represents time, and the Greek letter λ (lambda) represents what is commonly referred to as the parameter of the distribution. Depending on the value of λ, f(t) will be scaled differently. For any distribution, the parameter or parameters of the distribution are estimated from the data. For example, the well-known normal (or Gaussian) distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=\frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi }}{e}^{-\frac{1}{2}(\frac{t-\mu}{\sigma})^2} }[/math]

μ, the mean, and σ, the standard deviation, are its parameters. Both of these parameters are estimated from the data (i.e., the mean and standard deviation of the data). Once these parameters have been estimated, our function f(t) is fully defined and we can obtain any value for f(t) given any value of t.

Given the mathematical representation of a distribution, we can also derive all of the functions needed for life data analysis, which again will depend only on the value of t after the value of the distribution parameter or parameters have been estimated from data. For example, we know that the exponential distribution pdf is given by:

- f(t) = λe − λt

Thus, the exponential reliability function can be derived as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} R(t)= & 1-\int_{0}^{t}\lambda {{e}^{-\lambda s}}ds \\ = & 1-[ 1-{{e}^{-\lambda \cdot t}}] \\ = & {{e}^{-\lambda \cdot t}} \\ \end{align} }[/math]

The exponential failure rate function is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \lambda (t) =& \frac{f(t)}{R(t)} \\ =& \frac{\lambda {e}^{-\lambda t}}{e^{-\lambda t}} \\ =& \lambda \end{align} }[/math]

The exponential mean-time-to-failure (MTTF) is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mu = & \int_{0}^{\infty} t\cdot f(t)dt \\ = & \int_{0}^{\infty}{t \cdot {\lambda} \cdot e^{-\lambda t}}dt \\ = & \frac{1}{\lambda } \end{align} }[/math]

This exact same methodology can be applied to any distribution given its pdf, with various degrees of difficulty depending on the complexity of f(t).

Template loop detected: Template:ParameterTypes

The exponential distribution is a commonly used distribution in reliability engineering. Mathematically, it is a fairly simple distribution, which many times leads to its use in inappropriate situations. It is, in fact, a special case of the Weibull distribution where [math]\displaystyle{ \beta =1\,\! }[/math]. The exponential distribution is used to model the behavior of units that have a constant failure rate (or units that do not degrade with time or wear out).

Exponential Probability Density Function

The 2-Parameter Exponential Distribution

The 2-parameter exponential pdf is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=\lambda {{e}^{-\lambda (t-\gamma )}},f(t)\ge 0,\lambda \gt 0,t\ge \gamma \,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] is the location parameter. Some of the characteristics of the 2-parameter exponential distribution are discussed in Kececioglu [19]:

- The location parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math], if positive, shifts the beginning of the distribution by a distance of [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] to the right of the origin, signifying that the chance failures start to occur only after [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] hours of operation, and cannot occur before.

- The scale parameter is [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{\lambda }=\bar{t}-\gamma =m-\gamma \,\! }[/math].

- The exponential pdf has no shape parameter, as it has only one shape.

- The distribution starts at [math]\displaystyle{ t=\gamma \,\! }[/math] at the level of [math]\displaystyle{ f(t=\gamma )=\lambda \,\! }[/math] and decreases thereafter exponentially and monotonically as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases beyond [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] and is convex.

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t\to \infty \,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\to 0\,\! }[/math].

The 1-Parameter Exponential Distribution

The 1-parameter exponential pdf is obtained by setting [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma =0\,\! }[/math], and is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align}f(t)= & \lambda {{e}^{-\lambda t}}=\frac{1}{m}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{m}t}}, & t\ge 0, \lambda \gt 0,m\gt 0 \end{align} \,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math] = constant rate, in failures per unit of measurement, (e.g., failures per hour, per cycle, etc.)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda =\frac{1}{m}\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ m\,\! }[/math] = mean time between failures, or to failure

- [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] = operating time, life, or age, in hours, cycles, miles, actuations, etc.

This distribution requires the knowledge of only one parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math], for its application. Some of the characteristics of the 1-parameter exponential distribution are discussed in Kececioglu [19]:

- The location parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math], is zero.

- The scale parameter is [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{\lambda }=m\,\! }[/math].

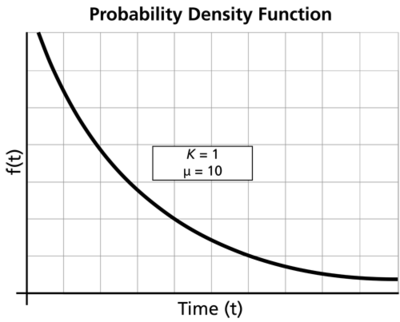

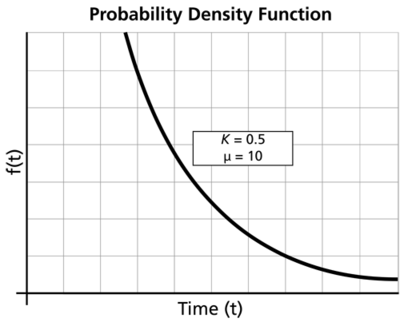

- As [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math] is decreased in value, the distribution is stretched out to the right, and as [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math] is increased, the distribution is pushed toward the origin.

- This distribution has no shape parameter as it has only one shape, (i.e., the exponential, and the only parameter it has is the failure rate, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math]).

- The distribution starts at [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math] at the level of [math]\displaystyle{ f(t=0)=\lambda \,\! }[/math] and decreases thereafter exponentially and monotonically as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases, and is convex.

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t\to \infty \,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\to 0\,\! }[/math].

- The pdf can be thought of as a special case of the Weibull pdf with [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma =0\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta =1\,\! }[/math].

Exponential Distribution Functions

The Mean or MTTF

The mean, [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{T},\,\! }[/math] or mean time to failure (MTTF) is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \bar{T}= & \int_{\gamma }^{\infty }t\cdot f(t)dt \\ = & \int_{\gamma }^{\infty }t\cdot \lambda \cdot {{e}^{-\lambda t}}dt \\ = & \gamma +\frac{1}{\lambda }=m \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Note that when [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma =0\,\! }[/math], the MTTF is the inverse of the exponential distribution's constant failure rate. This is only true for the exponential distribution. Most other distributions do not have a constant failure rate. Consequently, the inverse relationship between failure rate and MTTF does not hold for these other distributions.

The Median

The median, [math]\displaystyle{ \breve{T}, \,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \breve{T}=\gamma +\frac{1}{\lambda}\cdot 0.693 \,\! }[/math]

The Mode

The mode, [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{T},\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{T}=\gamma \,\! }[/math]

The Standard Deviation

The standard deviation, [math]\displaystyle{ {\sigma }_{T}\,\! }[/math], is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\sigma}_{T}=\frac{1}{\lambda }=m\,\! }[/math]

The Exponential Reliability Function

The equation for the 2-parameter exponential cumulative density function, or cdf, is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} F(t)=Q(t)=1-{{e}^{-\lambda (t-\gamma )}} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Recalling that the reliability function of a distribution is simply one minus the cdf, the reliability function of the 2-parameter exponential distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)=1-Q(t)=1-\int_{0}^{t-\gamma }f(x)dx\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)=1-\int_{0}^{t-\gamma }\lambda {{e}^{-\lambda x}}dx={{e}^{-\lambda (t-\gamma )}}\,\! }[/math]

The 1-parameter exponential reliability function is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)={{e}^{-\lambda t}}={{e}^{-\tfrac{t}{m}}}\,\! }[/math]

The Exponential Conditional Reliability Function

The exponential conditional reliability equation gives the reliability for a mission of [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] duration, having already successfully accumulated [math]\displaystyle{ T\,\! }[/math] hours of operation up to the start of this new mission. The exponential conditional reliability function is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t|T)=\frac{R(T+t)}{R(T)}=\frac{{{e}^{-\lambda (T+t-\gamma )}}}{{{e}^{-\lambda (T-\gamma )}}}={{e}^{-\lambda t}}\,\! }[/math]

which says that the reliability for a mission of [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] duration undertaken after the component or equipment has already accumulated [math]\displaystyle{ T\,\! }[/math] hours of operation from age zero is only a function of the mission duration, and not a function of the age at the beginning of the mission. This is referred to as the memoryless property.

The Exponential Reliable Life Function

The reliable life, or the mission duration for a desired reliability goal, [math]\displaystyle{ {{t}_{R}}\,\! }[/math], for the 1-parameter exponential distribution is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R({{t}_{R}})={{e}^{-\lambda ({{t}_{R}}-\gamma )}}\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \ln[R({{t}_{R}})]=-\lambda({{t}_{R}}-\gamma ) \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{t}_{R}}=\gamma -\frac{\ln [R({{t}_{R}})]}{\lambda }\,\! }[/math]

The Exponential Failure Rate Function

The exponential failure rate function is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda (t)=\frac{f(t)}{R(t)}=\frac{\lambda {{e}^{-\lambda (t-\gamma )}}}{{{e}^{-\lambda (t-\gamma )}}}=\lambda =\text{constant}\,\! }[/math]

Once again, note that the constant failure rate is a characteristic of the exponential distribution, and special cases of other distributions only. Most other distributions have failure rates that are functions of time.

Characteristics of the Exponential Distribution

The primary trait of the exponential distribution is that it is used for modeling the behavior of items with a constant failure rate. It has a fairly simple mathematical form, which makes it fairly easy to manipulate. Unfortunately, this fact also leads to the use of this model in situations where it is not appropriate. For example, it would not be appropriate to use the exponential distribution to model the reliability of an automobile. The constant failure rate of the exponential distribution would require the assumption that the automobile would be just as likely to experience a breakdown during the first mile as it would during the one-hundred-thousandth mile. Clearly, this is not a valid assumption. However, some inexperienced practitioners of reliability engineering and life data analysis will overlook this fact, lured by the siren-call of the exponential distribution's relatively simple mathematical models.

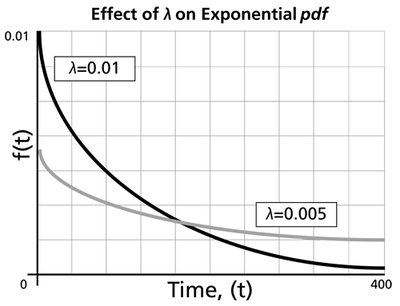

The Effect of lambda and gamma on the Exponential pdf

- The exponential pdf has no shape parameter, as it has only one shape.

- The exponential pdf is always convex and is stretched to the right as [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math] decreases in value.

- The value of the pdf function is always equal to the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \,\! }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ t=\gamma \,\! }[/math]).

- The location parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math], if positive, shifts the beginning of the distribution by a distance of [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] to the right of the origin, signifying that the chance failures start to occur only after [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math] hours of operation, and cannot occur before this time.

- The scale parameter is [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{\lambda }=\bar{T}-\gamma =m-\gamma \,\! }[/math].

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t\to \infty \,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\to 0\,\! }[/math].

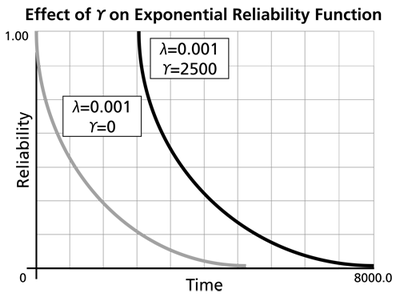

The Effect of lambda and gamma on the Exponential Reliability Function

- The 1-parameter exponential reliability function starts at the value of 100% at [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math], decreases thereafter monotonically and is convex.

- The 2-parameter exponential reliability function remains at the value of 100% for [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math] up to [math]\displaystyle{ t=\gamma \,\! }[/math], and decreases thereafter monotonically and is convex.

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t\to \infty \,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R(t\to \infty )\to 0\,\! }[/math].

- The reliability for a mission duration of [math]\displaystyle{ t=m=\tfrac{1}{\lambda }\,\! }[/math], or of one MTTF duration, is always equal to [math]\displaystyle{ 0.3679\,\! }[/math] or 36.79%. This means that the reliability for a mission which is as long as one MTTF is relatively low and is not recommended because only 36.8% of the missions will be completed successfully. In other words, of the equipment undertaking such a mission, only 36.8% will survive their mission.

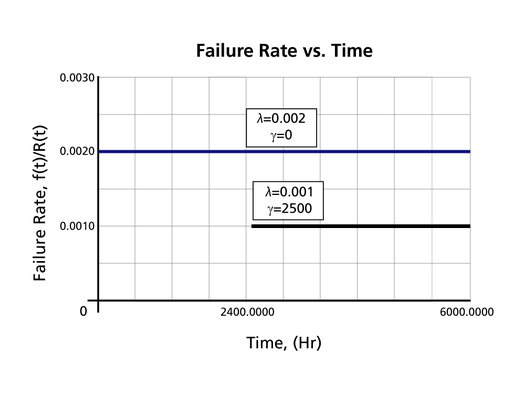

The Effect of lambda and gamma on the Failure Rate Function

- The 1-parameter exponential failure rate function is constant and starts at [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math].

- The 2-parameter exponential failure rate function remains at the value of 0 for [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math] up to [math]\displaystyle{ t=\gamma \,\! }[/math], and then keeps at the constant value of [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda\,\! }[/math].

Exponential Distribution Examples

Grouped Data

20 units were reliability tested with the following results:

| Table - Life Test Data | |

| Number of Units in Group | Time-to-Failure |

|---|---|

| 7 | 100 |

| 5 | 200 |

| 3 | 300 |

| 2 | 400 |

| 1 | 500 |

| 2 | 600 |

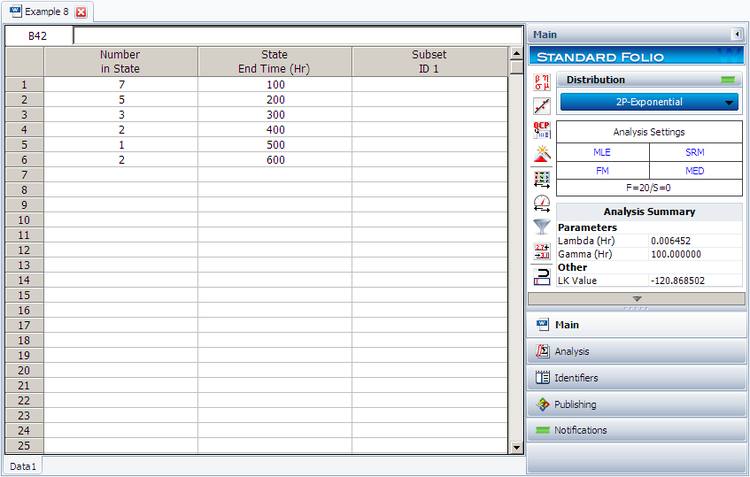

1. Assuming a 2-parameter exponential distribution, estimate the parameters by hand using the MLE analysis method.

2. Repeat the above using Weibull++. (Enter the data as grouped data to duplicate the results.)

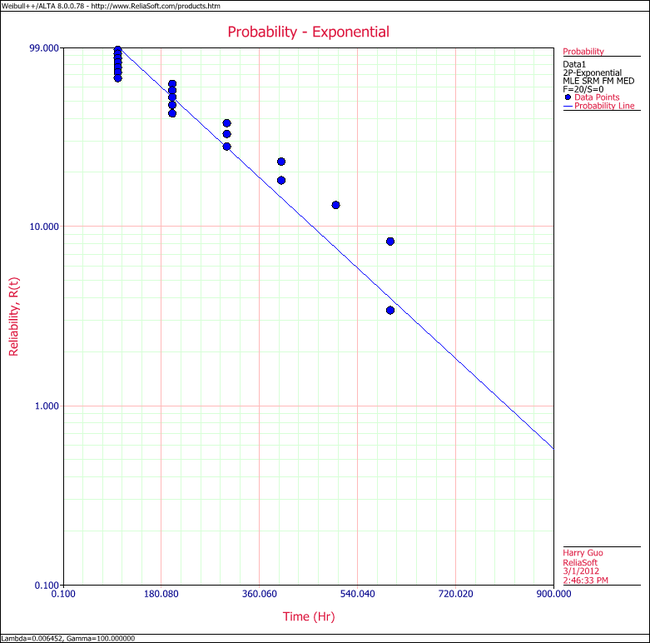

3. Show the Probability plot for the analysis results.

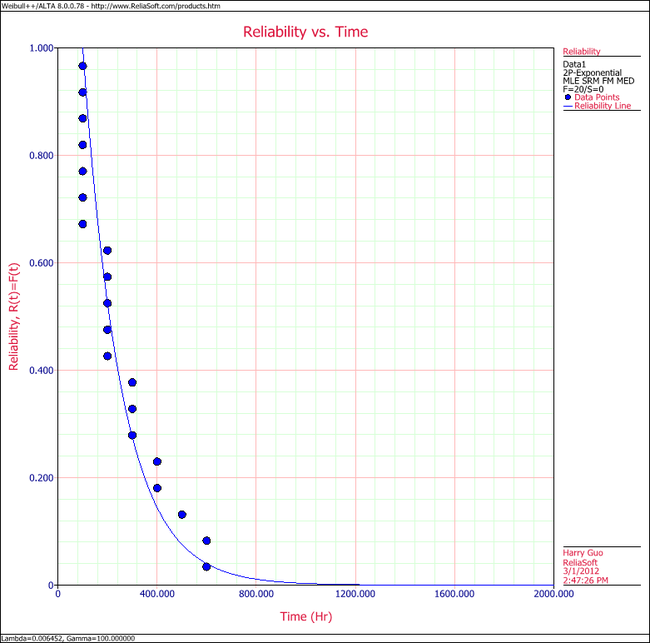

4. Show the Reliability vs. Time plot for the results.

5. Show the pdf plot for the results.

6. Show the Failure Rate vs. Time plot for the results.

7. Estimate the parameters using the rank regression on Y (RRY) analysis method (and using grouped ranks).

Solution

1. For the 2-parameter exponential distribution and for [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\gamma }=100\,\! }[/math] hours (first failure), the partial of the log-likelihood function, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda\,\! }[/math], becomes:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{\partial \Lambda }{\partial \lambda }= &\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop \sum }}\,{N_i} \left[ \frac{1}{\lambda }-\left( {{T}_{i}}-100 \right) \right]=0\\ \Rightarrow & 7[\frac{1}{\lambda }-(100-100)]+5[\frac{1}{\lambda}-(200-100)] + \ldots +2[\frac{1}{\lambda}-(600-100)]\\ = & 0\\ \Rightarrow & \hat{\lambda}=\frac{20}{3100}=0.0065 \text{fr/hr} \end{align} \,\! }[/math]

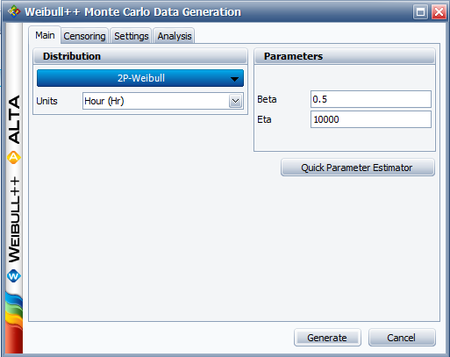

2. Enter the data in a Weibull++ standard folio and calculate it as shown next.

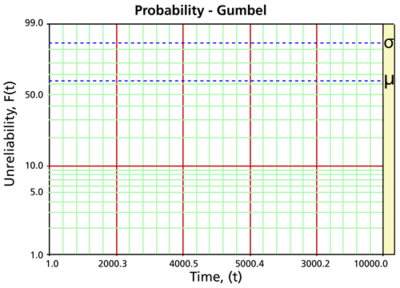

3. On the Plot page of the folio, the exponential Probability plot will appear as shown next.

4. View the Reliability vs. Time plot.

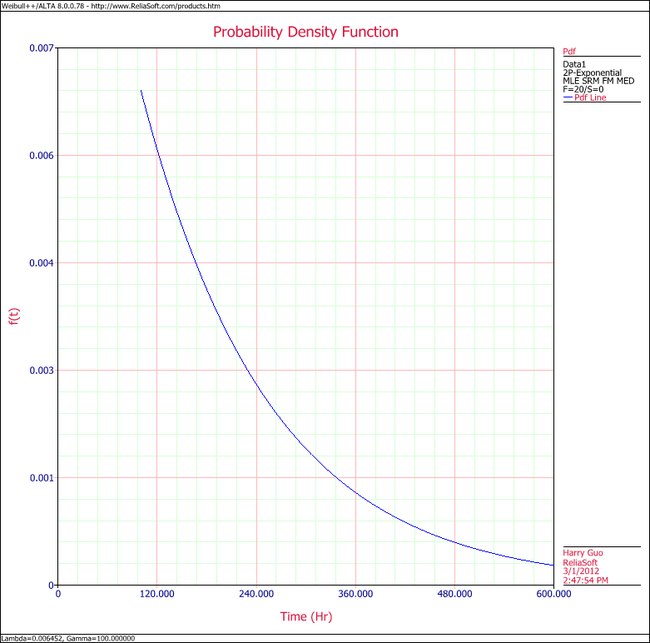

5. View the pdf plot.

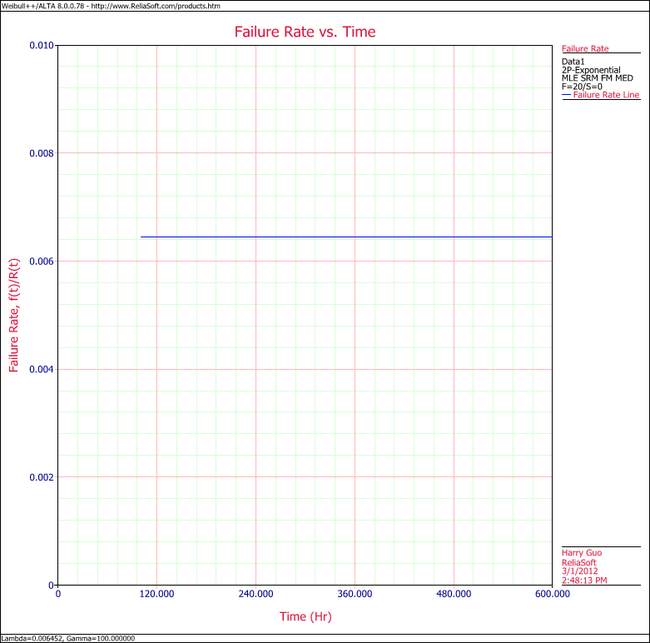

6. View the Failure Rate vs. Time plot.

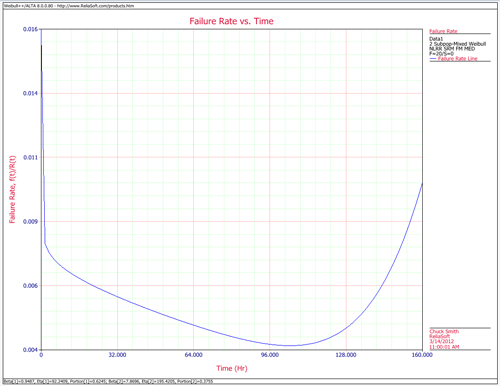

Note that, as described at the beginning of this chapter, the failure rate for the exponential distribution is constant. Also note that the Failure Rate vs. Time plot does show values for times before the location parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \,\! }[/math], at 100 hours.

7. In the case of grouped data, one must be cautious when estimating the parameters using a rank regression method. This is because the median rank values are determined from the total number of failures observed by time [math]\displaystyle{ {{T}_{i}}\,\! }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math] indicates the group number. In this example, the total number of groups is [math]\displaystyle{ N=6\,\! }[/math] and the total number of units is [math]\displaystyle{ {{N}_{T}}=20\,\! }[/math]. Thus, the median rank values will be estimated for 20 units and for the total failed units ([math]\displaystyle{ {{N}_{{{F}_{i}}}}\,\! }[/math]) up to the [math]\displaystyle{ {{i}^{th}}\,\! }[/math] group, for the [math]\displaystyle{ {{i}^{th}}\,\! }[/math] rank value. The median ranks values can be found from rank tables or they can be estimated using ReliaSoft's Quick Statistical Reference tool.

For example, the median rank value of the fourth group will be the [math]\displaystyle{ {{17}^{th}}\,\! }[/math] rank out of a sample size of twenty units (or 81.945%).

The following table is then constructed.

Given the values in the table above, calculate [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{a}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{b}\,\! }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{b}= & \frac{\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{t}_{i}}{{y}_{i}}-(\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{t}_{i}})(\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{y}_{i}})/6}{\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,t_{i}^{2}-{{(\underset{i=1}{\overset{6}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{t}_{i}})}^{2}}/6} \\ & & \\ & \hat{b}= & \frac{-4320.3362-(2100)(-9.6476)/6}{910,000-{{(2100)}^{2}}/6} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{b}=-0.005392\,\! }[/math]

and:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{a}=\overline{y}-\hat{b}\overline{t}=\frac{\underset{i=1}{\overset{N}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{y}_{i}}}{N}-\hat{b}\frac{\underset{i=1}{\overset{N}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{t}_{i}}}{N}\,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{a}=\frac{-9.6476}{6}-(-0.005392)\frac{2100}{6}=0.2793\,\! }[/math]

Therefore:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\lambda }=-\hat{b}=-(-0.005392)=0.05392\text{ failures/hour}\,\! }[/math]

and:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\gamma }=\frac{\hat{a}}{\hat{\lambda }}=\frac{0.2793}{0.005392}\,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\gamma }\simeq 51.8\text{ hours}\,\! }[/math]

Then:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(T)=(0.005392){{e}^{-0.005392(T-51.8)}}\,\! }[/math]

Using Weibull++, the estimated parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \hat{\lambda }= & 0.0054\text{ failures/hour} \\ \hat{\gamma }= & 51.82\text{ hours} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The small difference in the values from Weibull++ is due to rounding. In the application, the calculations and the rank values are carried out up to the [math]\displaystyle{ 15^{th}\,\! }[/math] decimal point.

Using Auto Batch Run

A number of leukemia patients were treated with either drug 6MP or a placebo, and the times in weeks until cancer symptoms returned were recorded. Analyze each treatment separately [21, p.175].

| Table - Leukemia Treatment Results | |||

| Time (weeks) | Number of Patients | Treament | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | placebo | |

| 2 | 2 | placebo | |

| 3 | 1 | placebo | |

| 4 | 2 | placebo | |

| 5 | 2 | placebo | |

| 6 | 4 | 6MP | 3 patients completed |

| 7 | 1 | 6MP | |

| 8 | 4 | placebo | |

| 9 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 10 | 2 | 6MP | 1 patient completed |

| 11 | 2 | placebo | |

| 11 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 12 | 2 | placebo | |

| 13 | 1 | 6MP | |

| 15 | 1 | placebo | |

| 16 | 1 | 6MP | |

| 17 | 1 | placebo | |

| 17 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 19 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 20 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 22 | 1 | placebo | |

| 22 | 1 | 6MP | |

| 23 | 1 | placebo | |

| 23 | 1 | 6MP | |

| 25 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 32 | 2 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 34 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

| 35 | 1 | 6MP | Not completed |

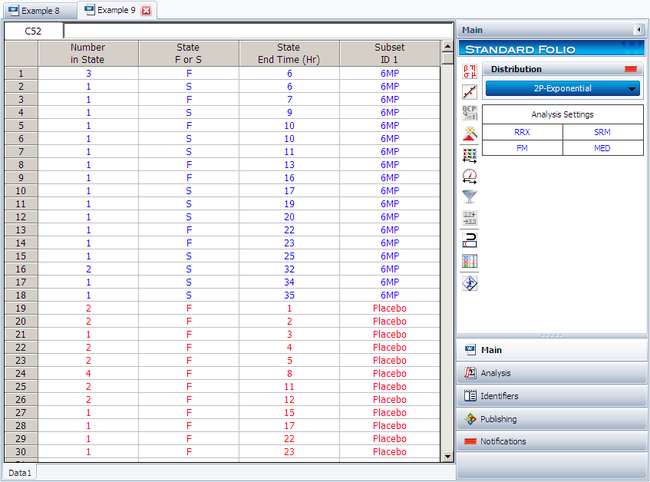

Create a new Weibull++ standard folio that's configured for grouped times-to-failure data with suspensions. In the first column, enter the number of patients. Whenever there are uncompleted tests, enter the number of patients who completed the test separately from the number of patients who did not (e.g., if 4 patients had symptoms return after 6 weeks and only 3 of them completed the test, then enter 1 in one row and 3 in another). In the second column enter F if the patients completed the test and S if they didn't. In the third column enter the time, and in the fourth column (Subset ID) specify whether the 6MP drug or a placebo was used.

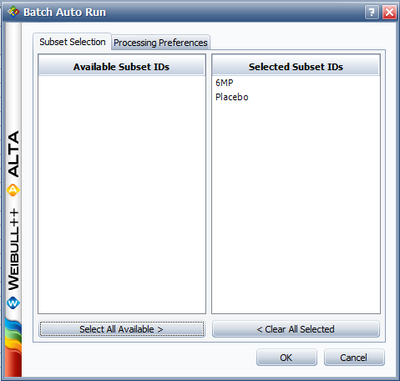

Next, open the Batch Auto Run utility and select to separate the 6MP drug from the placebo, as shown next.

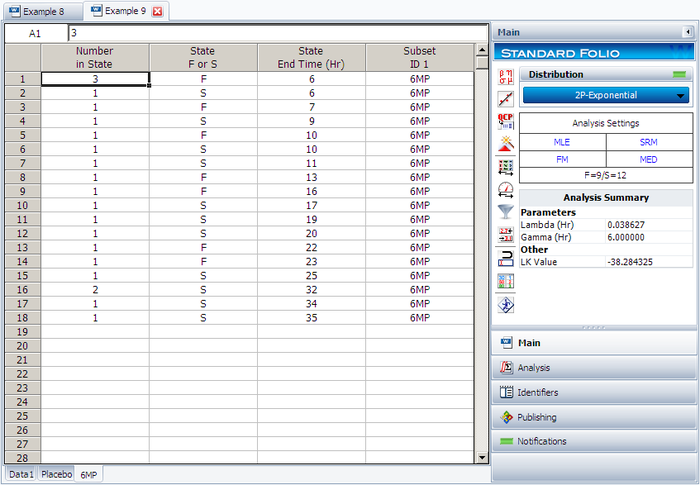

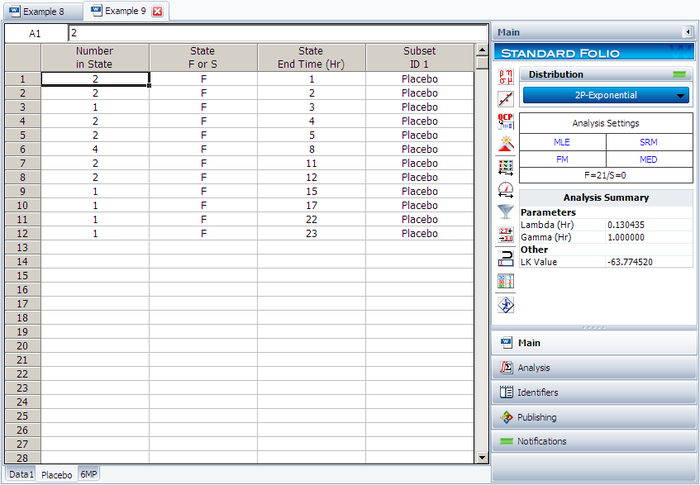

The software will create two data sheets, one for each subset ID, as shown next.

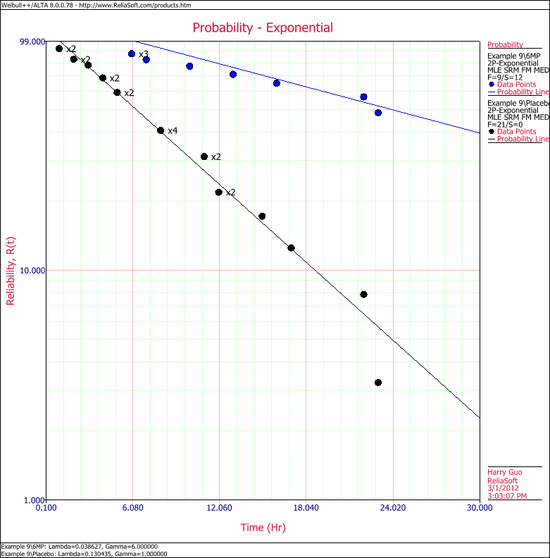

Calculate both data sheets using the 2-parameter exponential distribution and the MLE analysis method, then insert an additional plot and select to show the analysis results for both data sheets on that plot, which will appear as shown next.

The Weibull distribution is one of the most widely used lifetime distributions in reliability engineering. It is a versatile distribution that can take on the characteristics of other types of distributions, based on the value of the shape parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ {\beta} \,\! }[/math]. This chapter provides a brief background on the Weibull distribution, presents and derives most of the applicable equations and presents examples calculated both manually and by using ReliaSoft's Weibull++ software.

Weibull Probability Density Function

The 3-Parameter Weibull

The 3-parameter Weibull pdf is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)={ \frac{\beta }{\eta }}\left( {\frac{t-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta -1}e^{-\left( {\frac{t-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\geq 0,\text{ }t\geq \gamma \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\gt 0\ \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \eta \gt 0 \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ -\infty \lt \gamma \lt +\infty \,\! }[/math]

and:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \eta= \,\! }[/math] scale parameter, or characteristic life

- [math]\displaystyle{ \beta= \,\! }[/math] shape parameter (or slope)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma= \,\! }[/math] location parameter (or failure free life)

The 2-Parameter Weibull

The 2-parameter Weibull pdf is obtained by setting [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma=0 \,\! }[/math], and is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)={ \frac{\beta }{\eta }}\left( {\frac{t}{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta -1}e^{-\left( { \frac{t}{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

The 1-Parameter Weibull

The 1-parameter Weibull pdf is obtained by again setting [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma=0 \,\! }[/math] and assuming [math]\displaystyle{ \beta=C=Constant \,\! }[/math] assumed value or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)={ \frac{C}{\eta }}\left( {\frac{t}{\eta }}\right) ^{C-1}e^{-\left( {\frac{t}{ \eta }}\right) ^{C}} \,\! }[/math]

where the only unknown parameter is the scale parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math].

Note that in the formulation of the 1-parameter Weibull, we assume that the shape parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \,\! }[/math] is known a priori from past experience with identical or similar products. The advantage of doing this is that data sets with few or no failures can be analyzed.

Weibull Distribution Functions

The Mean or MTTF

The mean, [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{T} \,\! }[/math], (also called MTTF) of the Weibull pdf is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{T}=\gamma +\eta \cdot \Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{\beta }}+1\right) \,\! }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{\beta }}+1\right) \,\! }[/math]

is the gamma function evaluated at the value of:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left( { \frac{1}{\beta }}+1\right) \,\! }[/math]

The gamma function is defined as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma (n)=\int_{0}^{\infty }e^{-x}x^{n-1}dx \,\! }[/math]

For the 2-parameter case, this can be reduced to:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{T}=\eta \cdot \Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{\beta }}+1\right) \,\! }[/math]

Note that some practitioners erroneously assume that [math]\displaystyle{ \eta \,\! }[/math] is equal to the MTTF, [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{T}\,\! }[/math]. This is only true for the case of: [math]\displaystyle{ \beta=1 \,\! }[/math] or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \overline{T} &= \eta \cdot \Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{1}}+1\right) \\ &= \eta \cdot \Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{1}}+1\right) \\ &= \eta \cdot \Gamma \left( {2}\right) \\ &= \eta \cdot 1\\ &= \eta \end{align} \,\! }[/math]

The Median

The median, [math]\displaystyle{ \breve{T}\,\! }[/math], of the Weibull distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \breve{T}=\gamma +\eta \left( \ln 2\right) ^{\frac{1}{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

The Mode

The mode, [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{T} \,\! }[/math], is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{T}=\gamma +\eta \left( 1-\frac{1}{\beta }\right) ^{\frac{1}{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

The Standard Deviation

The standard deviation, [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma _{T}\,\! }[/math], is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma _{T}=\eta \cdot \sqrt{\Gamma \left( {\frac{2}{\beta }}+1\right) -\Gamma \left( {\frac{1}{ \beta }}+1\right) ^{2}} \,\! }[/math]

The Weibull Reliability Function

The equation for the 3-parameter Weibull cumulative density function, cdf, is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(t)=1-e^{-\left( \frac{t-\gamma }{\eta }\right) ^{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

This is also referred to as unreliability and designated as [math]\displaystyle{ Q(t) \,\! }[/math] by some authors.

Recalling that the reliability function of a distribution is simply one minus the cdf, the reliability function for the 3-parameter Weibull distribution is then given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)=e^{-\left( { \frac{t-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

The Weibull Conditional Reliability Function

The 3-parameter Weibull conditional reliability function is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t|T)={ \frac{R(T+t)}{R(T)}}={\frac{e^{-\left( {\frac{T+t-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }}}{e^{-\left( {\frac{T-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }}}} \,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t|T)=e^{-\left[ \left( {\frac{T+t-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }-\left( {\frac{T-\gamma }{\eta }}\right) ^{\beta }\right] } \,\! }[/math]

These give the reliability for a new mission of [math]\displaystyle{ t \,\! }[/math] duration, having already accumulated [math]\displaystyle{ T \,\! }[/math] time of operation up to the start of this new mission, and the units are checked out to assure that they will start the next mission successfully. It is called conditional because you can calculate the reliability of a new mission based on the fact that the unit or units already accumulated hours of operation successfully.

The Weibull Reliable Life

The reliable life, [math]\displaystyle{ T_{R}\,\! }[/math], of a unit for a specified reliability, [math]\displaystyle{ R\,\! }[/math], starting the mission at age zero, is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ T_{R}=\gamma +\eta \cdot \left\{ -\ln ( R ) \right\} ^{ \frac{1}{\beta }} \,\! }[/math]

This is the life for which the unit/item will be functioning successfully with a reliability of [math]\displaystyle{ R\,\! }[/math]. If [math]\displaystyle{ R = 0.50\,\! }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ T_{R}=\breve{T} \,\! }[/math], the median life, or the life by which half of the units will survive.

The Weibull Failure Rate Function

The Weibull failure rate function, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t) \,\! }[/math], is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \left( t\right) = \frac{f\left( t\right) }{R\left( t\right) }=\frac{\beta }{\eta }\left( \frac{ t-\gamma }{\eta }\right) ^{\beta -1} \,\! }[/math]

Characteristics of the Weibull Distribution

The Weibull distribution is widely used in reliability and life data analysis due to its versatility. Depending on the values of the parameters, the Weibull distribution can be used to model a variety of life behaviors. We will now examine how the values of the shape parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math], and the scale parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math], affect such distribution characteristics as the shape of the curve, the reliability and the failure rate. Note that in the rest of this section we will assume the most general form of the Weibull distribution, (i.e., the 3-parameter form). The appropriate substitutions to obtain the other forms, such as the 2-parameter form where [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma = 0,\,\! }[/math] or the 1-parameter form where [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = C = \,\! }[/math] constant, can easily be made.

Effects of the Shape Parameter, beta

The Weibull shape parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math], is also known as the slope. This is because the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] is equal to the slope of the regressed line in a probability plot. Different values of the shape parameter can have marked effects on the behavior of the distribution. In fact, some values of the shape parameter will cause the distribution equations to reduce to those of other distributions. For example, when [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 1\,\! }[/math], the pdf of the 3-parameter Weibull distribution reduces to that of the 2-parameter exponential distribution or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)={\frac{1}{\eta }}e^{-{\frac{t-\gamma }{\eta }}} \,\! }[/math]

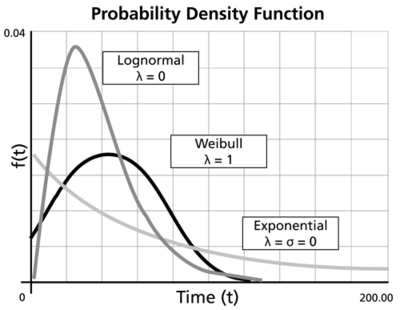

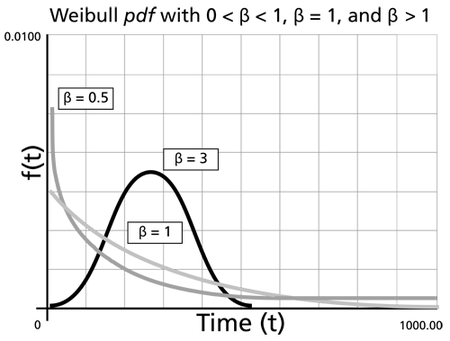

where [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{\eta }=\lambda = \,\! }[/math] failure rate. The parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] is a pure number, (i.e., it is dimensionless). The following figure shows the effect of different values of the shape parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math], on the shape of the pdf. As you can see, the shape can take on a variety of forms based on the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math].

For [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \beta \leq 1 \,\! }[/math]:

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t \rightarrow 0\,\! }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\rightarrow \infty.\,\! }[/math]

- As [math]\displaystyle{ t\rightarrow \infty\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\rightarrow 0\,\! }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\,\! }[/math] decreases monotonically and is convex as it increases beyond the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math].

- The mode is non-existent.

For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 1 \,\! }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t) = 0\,\! }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ t = 0\,\! }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math]).

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\,\! }[/math] increases as [math]\displaystyle{ t\rightarrow \tilde{T} \,\! }[/math] (the mode) and decreases thereafter.

- For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \lt 2.6\,\! }[/math] the Weibull pdf is positively skewed (has a right tail), for [math]\displaystyle{ 2.6 \lt \beta \lt 3.7\,\! }[/math] its coefficient of skewness approaches zero (no tail). Consequently, it may approximate the normal pdf, and for [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 3.7\,\! }[/math] it is negatively skewed (left tail). The way the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] relates to the physical behavior of the items being modeled becomes more apparent when we observe how its different values affect the reliability and failure rate functions. Note that for [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 0.999\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(0) = \infty\,\! }[/math], but for [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 1.001\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(0) = 0.\,\! }[/math] This abrupt shift is what complicates MLE estimation when [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] is close to 1.

The Effect of beta on the cdf and Reliability Function

The above figure shows the effect of the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] on the cdf, as manifested in the Weibull probability plot. It is easy to see why this parameter is sometimes referred to as the slope. Note that the models represented by the three lines all have the same value of [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math]. The following figure shows the effects of these varied values of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] on the reliability plot, which is a linear analog of the probability plot.

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)\,\! }[/math] decreases sharply and monotonically for [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt \beta \lt 1\,\! }[/math] and is convex.

- For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 1\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)\,\! }[/math] decreases monotonically but less sharply than for [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt \beta \lt 1\,\! }[/math] and is convex.

- For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 1\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)\,\! }[/math] decreases as increases. As wear-out sets in, the curve goes through an inflection point and decreases sharply.

The Effect of beta on the Weibull Failure Rate

The value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] has a marked effect on the failure rate of the Weibull distribution and inferences can be drawn about a population's failure characteristics just by considering whether the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] is less than, equal to, or greater than one.

As indicated by above figure, populations with [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \lt 1\,\! }[/math] exhibit a failure rate that decreases with time, populations with [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 1\,\! }[/math] have a constant failure rate (consistent with the exponential distribution) and populations with [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 1\,\! }[/math] have a failure rate that increases with time. All three life stages of the bathtub curve can be modeled with the Weibull distribution and varying values of [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math]. The Weibull failure rate for [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt \beta \lt 1\,\! }[/math] is unbounded at [math]\displaystyle{ T = 0\,\! }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\!)\,\! }[/math]. The failure rate, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t),\,\! }[/math] decreases thereafter monotonically and is convex, approaching the value of zero as [math]\displaystyle{ t\rightarrow \infty\,\! }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda (\infty) = 0\,\! }[/math]. This behavior makes it suitable for representing the failure rate of units exhibiting early-type failures, for which the failure rate decreases with age. When encountering such behavior in a manufactured product, it may be indicative of problems in the production process, inadequate burn-in, substandard parts and components, or problems with packaging and shipping. For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 1\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] yields a constant value of [math]\displaystyle{ { \frac{1}{\eta }} \,\! }[/math] or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda (t)=\lambda ={\frac{1}{\eta }} \,\! }[/math]

This makes it suitable for representing the failure rate of chance-type failures and the useful life period failure rate of units.

For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 1\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] increases as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases and becomes suitable for representing the failure rate of units exhibiting wear-out type failures. For [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \lt \beta \lt 2,\,\! }[/math] the [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] curve is concave, consequently the failure rate increases at a decreasing rate as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases.

For [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 2\,\! }[/math] there emerges a straight line relationship between [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math], starting at a value of [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t) = 0\,\! }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ t = \gamma\,\! }[/math], and increasing thereafter with a slope of [math]\displaystyle{ { \frac{2}{\eta ^{2}}} \,\! }[/math]. Consequently, the failure rate increases at a constant rate as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases. Furthermore, if [math]\displaystyle{ \eta = 1\,\! }[/math] the slope becomes equal to 2, and when [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma = 0\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] becomes a straight line which passes through the origin with a slope of 2. Note that at [math]\displaystyle{ \beta = 2\,\! }[/math], the Weibull distribution equations reduce to that of the Rayleigh distribution.

When [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 2,\,\! }[/math] the [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(t)\,\! }[/math] curve is convex, with its slope increasing as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases. Consequently, the failure rate increases at an increasing rate as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases, indicating wearout life.

Effects of the Scale Parameter, eta

A change in the scale parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math] has the same effect on the distribution as a change of the abscissa scale. Increasing the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math] while holding [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] constant has the effect of stretching out the pdf. Since the area under a pdf curve is a constant value of one, the "peak" of the pdf curve will also decrease with the increase of [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math], as indicated in the above figure.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math] is increased while [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] are kept the same, the distribution gets stretched out to the right and its height decreases, while maintaining its shape and location.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math] is decreased while [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] are kept the same, the distribution gets pushed in towards the left (i.e., towards its beginning or towards 0 or [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math]), and its height increases.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\,\! }[/math] has the same units as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math], such as hours, miles, cycles, actuations, etc.

Effects of the Location Parameter, gamma

The location parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math], as the name implies, locates the distribution along the abscissa. Changing the value of [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] has the effect of sliding the distribution and its associated function either to the right (if [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \gt 0\,\! }[/math]) or to the left (if [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \lt 0\,\! }[/math]).

- When [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma = 0,\,\! }[/math] the distribution starts at [math]\displaystyle{ t=0\,\! }[/math] or at the origin.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \gt 0,\,\! }[/math] the distribution starts at the location [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] to the right of the origin.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \lt 0,\,\! }[/math] the distribution starts at the location [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] to the left of the origin.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] provides an estimate of the earliest time-to-failure of such units.

- The life period 0 to [math]\displaystyle{ + \gamma\,\! }[/math] is a failure free operating period of such units.

- The parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] may assume all values and provides an estimate of the earliest time a failure may be observed. A negative [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] may indicate that failures have occurred prior to the beginning of the test, namely during production, in storage, in transit, during checkout prior to the start of a mission, or prior to actual use.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\,\! }[/math] has the same units as [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math], such as hours, miles, cycles, actuations, etc.

Weibull Distribution Examples

Median Rank Plot Example

In this example, we will determine the median rank value used for plotting the 6th failure from a sample size of 10. This example will use Weibull++'s Quick Statistical Reference (QSR) tool to show how the points in the plot of the following example are calculated.

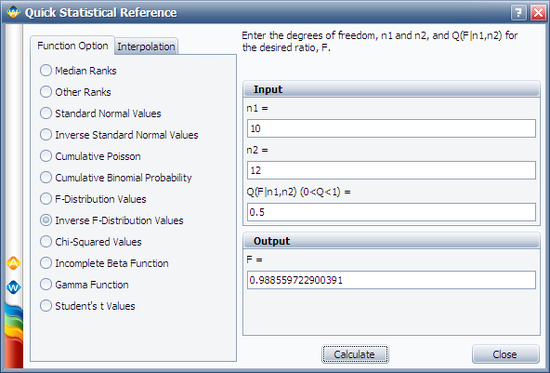

First, open the Quick Statistical Reference tool and select the Inverse F-Distribution Values option.

In this example, n1 = 10, j = 6, m = 2(10 - 6 + 1) = 10, and n2 = 2 x 6 = 12.

Thus, from the F-distribution rank equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ MR=\frac{1}{1+\left( \frac{10-6+1}{6} \right){{F}_{0.5;10;12}}}\,\! }[/math]

Use the QSR to calculate the value of F0.5;10;12 = 0.9886, as shown next:

Consequently:

- [math]\displaystyle{ MR=\frac{1}{1+\left( \frac{5}{6} \right)\times 0.9886}=0.5483=54.83%\,\! }[/math]

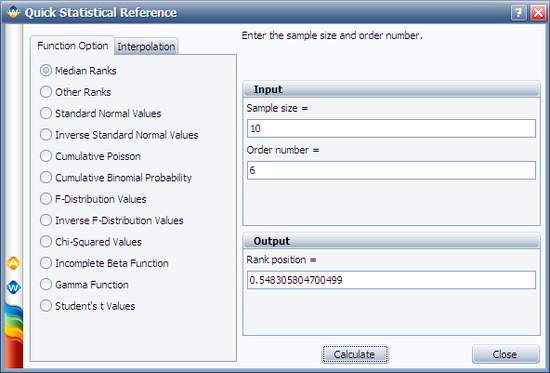

Another method is to use the Median Ranks option directly, which yields MR(%) = 54.8305%, as shown next:

Complete Data Example

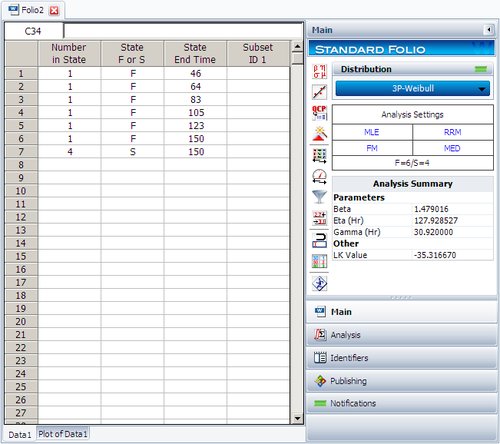

Assume that 10 identical units (N = 10) are being reliability tested at the same application and operation stress levels. 6 of these units fail during this test after operating the following numbers of hours, [math]\displaystyle{ {T}_{j}\,\! }[/math]: 150, 105, 83, 123, 64 and 46. The test is stopped at the 6th failure. Find the parameters of the Weibull pdf that represents these data.

Solution

Create a new Weibull++ standard folio that is configured for grouped times-to-failure data with suspensions.

Enter the data in the appropriate columns. Note that there are 4 suspensions, as only 6 of the 10 units were tested to failure (the next figure shows the data as entered). Use the 3-parameter Weibull and MLE for the calculations.

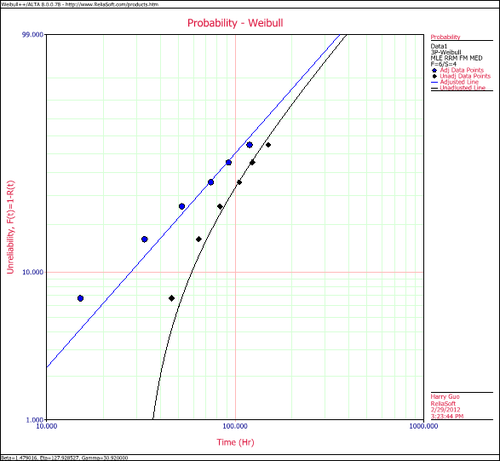

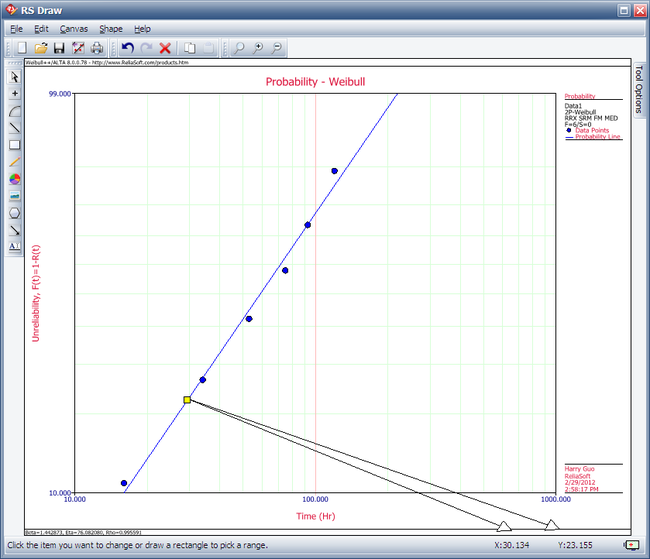

Plot the data.

Note that the original data points, on the curved line, were adjusted by subtracting 30.92 hours to yield a straight line as shown above.

Suspension Data Example

ACME company manufactures widgets, and it is currently engaged in reliability testing a new widget design. 19 units are being reliability tested, but due to the tremendous demand for widgets, units are removed from the test whenever the production cannot cover the demand. The test is terminated at the 67th day when the last widget is removed from the test. The following table contains the collected data.

| Data Point Index | State (F/S) | Time to Failure |

| 1 | F | 2 |

| 2 | S | 3 |

| 3 | F | 5 |

| 4 | S | 7 |

| 5 | F | 11 |

| 6 | S | 13 |

| 7 | S | 17 |

| 8 | S | 19 |

| 9 | F | 23 |

| 10 | F | 29 |

| 11 | S | 31 |

| 12 | F | 37 |

| 13 | S | 41 |

| 14 | F | 43 |

| 15 | S | 47 |

| 16 | S | 53 |

| 17 | F | 59 |

| 18 | S | 61 |

| 19 | S | 67 |

Solution

In this example, we see that the number of failures is less than the number of suspensions. This is a very common situation, since reliability tests are often terminated before all units fail due to financial or time constraints. Furthermore, some suspensions will be recorded when a failure occurs that is not due to a legitimate failure mode, such as operator error. In cases such as this, a suspension is recorded, since the unit under test cannot be said to have had a legitimate failure.

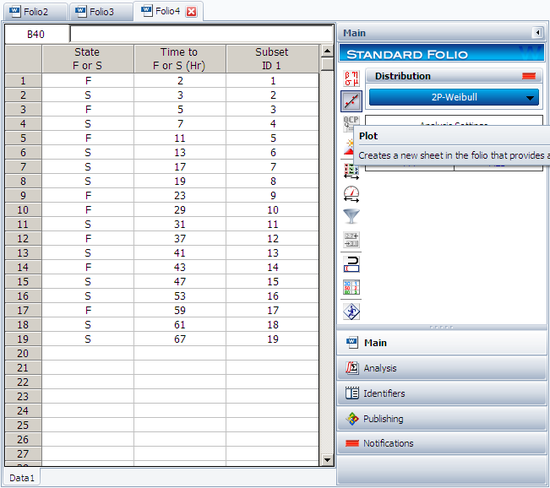

Enter the data into a Weibull++ standard folio that is configured for times-to-failure data with suspensions. The folio will appear as shown next:

We will use the 2-parameter Weibull to solve this problem. The parameters using maximum likelihood are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=1.145 \\ & \hat{\eta }=65.97 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Using RRX:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=0.914\\ & \hat{\eta }=79.38 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Using RRY:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=0.895\\ & \hat{\eta }=82.02 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Interval Data Example

Suppose we have run an experiment with 8 units tested and the following is a table of their last inspection times and failure times:

| Data Point Index | Last Inspection | Failure Time |

| 1 | 30 | 32 |

| 2 | 32 | 35 |

| 3 | 35 | 37 |

| 4 | 37 | 40 |

| 5 | 42 | 42 |

| 6 | 45 | 45 |

| 7 | 50 | 50 |

| 8 | 55 | 55 |

Analyze the data using several different parameter estimation techniques and compare the results.

Solution

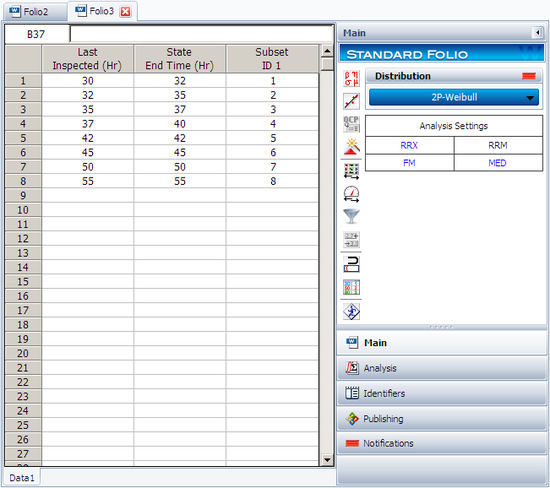

Enter the data into a Weibull++ standard folio that is configured for interval data. The data is entered as follows:

The computed parameters using maximum likelihood are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=5.76 \\ & \hat{\eta }=44.68 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Using RRX or rank regression on X:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=5.70 \\ & \hat{\eta }=44.54 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Using RRY or rank regression on Y:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{\beta }=5.41 \\ & \hat{\eta }=44.76 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

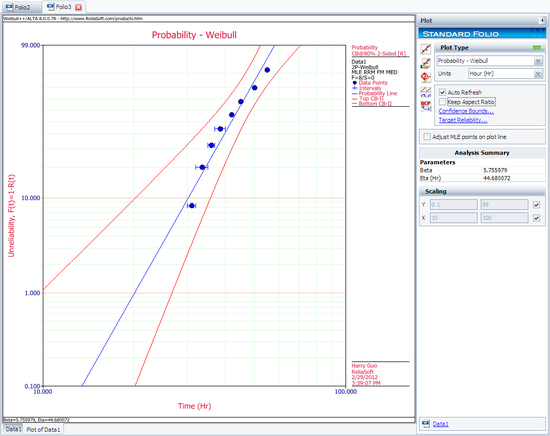

The plot of the MLE solution with the two-sided 90% confidence bounds is:

Mixed Data Types Example

From Dimitri Kececioglu, Reliability & Life Testing Handbook, Page 406. [20].

Estimate the parameters for the 3-parameter Weibull, for a sample of 10 units that are all tested to failure. The recorded failure times are 200; 370; 500; 620; 730; 840; 950; 1,050; 1,160 and 1,400 hours.

Published Results:

Published results (using probability plotting):

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\beta}} = 3.0\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\eta}} = 1,220\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\gamma}} = -300\,\! }[/math]

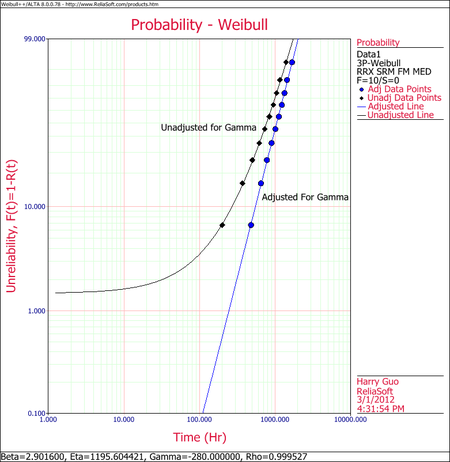

Computed Results in Weibull++

Weibull++ computed parameters for rank regression on X are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\beta}} = 2.9013\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\eta}} = 1195.5009\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat{\gamma}} = -279.000\,\! }[/math]

The small difference between the published results and the ones obtained from Weibull++ are due to the difference in the estimation method. In the publication the parameters were estimated using probability plotting (i.e., the fitted line was "eye-balled"). In Weibull++, the parameters were estimated using non-linear regression (a more accurate, mathematically fitted line). Note that γ in this example is negative. This means that the unadjusted for γ line is concave up, as shown next.

Weibull Distribution RRX Example

Assume that 6 identical units are being tested. The failure times are: 93, 34, 16, 120, 53 and 75 hours.

1. What is the unreliability of the units for a mission duration of 30 hours, starting the mission at age zero?

2. What is the reliability for a mission duration of 10 hours, starting the new mission at the age of T = 30 hours?

3. What is the longest mission that this product should undertake for a reliability of 90%?

Solution

1. First, we use Weibull++ to obtain the parameters using RRX.

Then, we investigate several methods of solution for this problem. The first, and more laborious, method is to extract the information directly from the plot. You may do this with either the screen plot in RS Draw or the printed copy of the plot. (When extracting information from the screen plot in RS Draw, note that the translated axis position of your mouse is always shown on the bottom right corner.)

Using this first method, enter either the screen plot or the printed plot with T = 30 hours, go up vertically to the straight line fitted to the data, then go horizontally to the ordinate, and read off the result. A good estimate of the unreliability is 23%. (Also, the reliability estimate is 1.0 - 0.23 = 0.77 or 77%.)

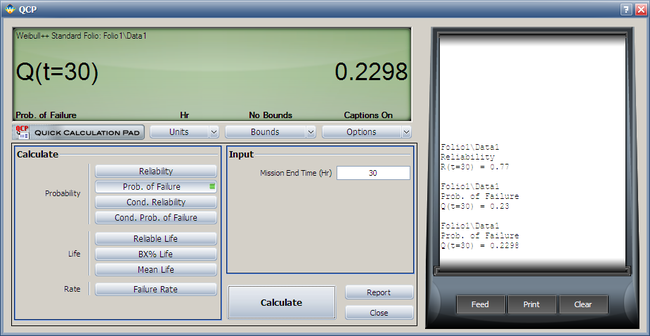

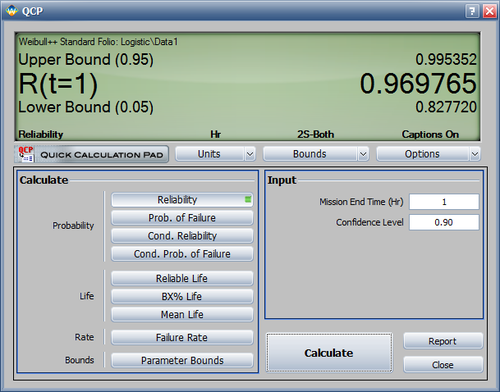

The second method involves the use of the Quick Calculation Pad (QCP).

Select the Prob. of Failure calculation option and enter 30 hours in the Mission End Time field.

Note that the results in QCP vary according to the parameter estimation method used. The above results are obtained using RRX.

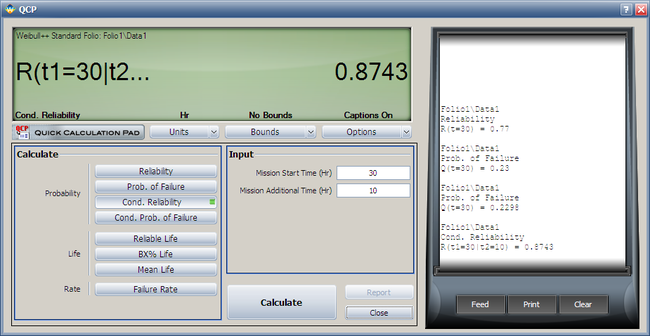

2. The conditional reliability is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t|T)=\frac{R(T+t)}{R(T)}\,\! }[/math]

or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{R}(10hr|30hr)=\frac{\hat{R}(10+30)}{\hat{R}(30)}=\frac{\hat{R}(40)}{\hat{R}(30)}\,\! }[/math]

Again, the QCP can provide this result directly and more accurately than the plot.

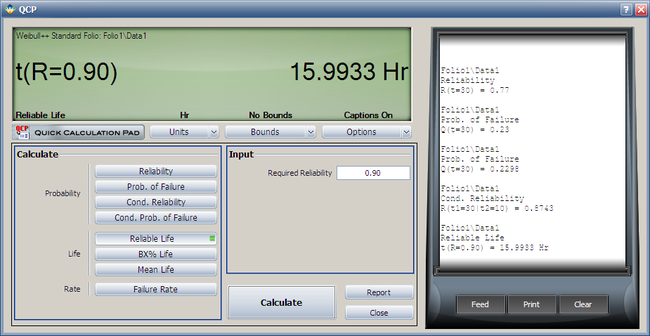

3. To use the QCP to solve for the longest mission that this product should undertake for a reliability of 90%, choose Reliable Life and enter 0.9 for the required reliability. The result is 15.9933 hours.

Benchmark with Published Examples

The following examples compare published results to computed results obtained with Weibull++.

Complete Data RRY Example

From Dimitri Kececioglu, Reliability & Life Testing Handbook, Page 418 [20].

Sample of 10 units, all tested to failure. The failures were recorded at 16, 34, 53, 75, 93, 120, 150, 191, 240 and 339 hours.

Published Results

Published Results (using Rank Regression on Y):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.20 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 146.2 \\ & \hat{\rho }=0.998703\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Computed Results in Weibull++

This same data set can be entered into a Weibull++ standard data sheet. Use RRY for the estimation method.

Weibull++ computed parameters for RRY are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.1973 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 146.2545 \\ & \hat{\rho }=0.9999\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The small difference between the published results and the ones obtained from Weibull++ is due to the difference in the median rank values between the two (in the publication, median ranks are obtained from tables to 3 decimal places, whereas in Weibull++ they are calculated and carried out up to the 15th decimal point).

You will also notice that in the examples that follow, a small difference may exist between the published results and the ones obtained from Weibull++. This can be attributed to the difference between the computer numerical precision employed by Weibull++ and the lower number of significant digits used by the original authors. In most of these publications, no information was given as to the numerical precision used.

Suspension Data MLE Example

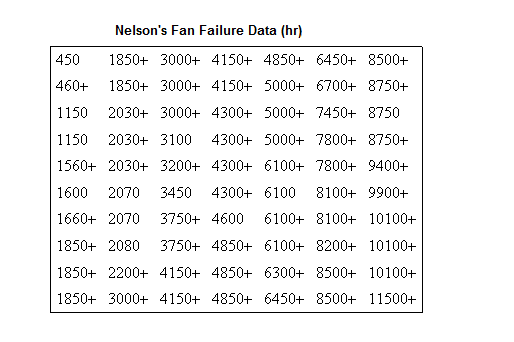

From Wayne Nelson, Fan Example, Applied Life Data Analysis, page 317 [30].

70 diesel engine fans accumulated 344,440 hours in service and 12 of them failed. A table of their life data is shown next (+ denotes non-failed units or suspensions, using Dr. Nelson's nomenclature). Evaluate the parameters with their two-sided 95% confidence bounds, using MLE for the 2-parameter Weibull distribution.

Published Results:

Weibull parameters (2P-Weibull, MLE):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.0584 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 26,296 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Published 95% FM confidence limits on the parameters:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=\lbrace 0.6441, \text{ }1.7394\rbrace \\ & \widehat{\eta} = \lbrace 10,522, \text{ }65,532\rbrace \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

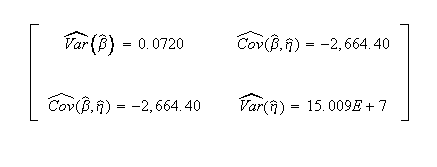

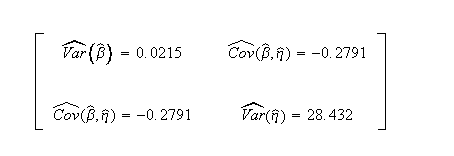

Published variance/covariance matrix:

Note that Nelson expresses the results as multiples of 1,000 (or = 26.297, etc.). The published results were adjusted by this factor to correlate with Weibull++ results.

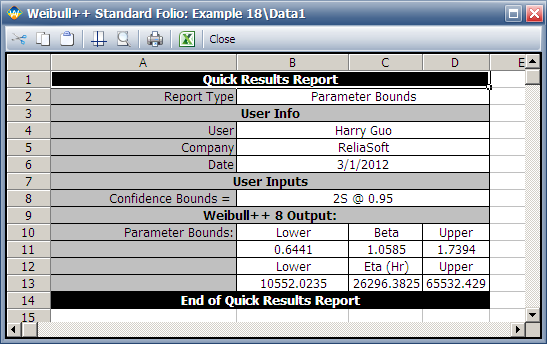

Computed Results in Weibull++

This same data set can be entered into a Weibull++ standard folio, using 2-parameter Weibull and MLE to calculate the parameter estimates.

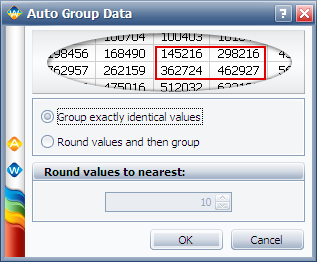

You can also enter the data as given in table without grouping them by opening a data sheet configured for suspension data. Then click the Group Data icon and chose Group exactly identical values.

The data will be automatically grouped and put into a new grouped data sheet.

Weibull++ computed parameters for maximum likelihood are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.0584 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 26,297 \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Weibull++ computed 95% FM confidence limits on the parameters:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=\lbrace 0.6441, \text{ }1.7394\rbrace \\ & \widehat{\eta} = \lbrace 10,522, \text{ }65,532\rbrace \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

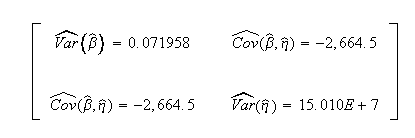

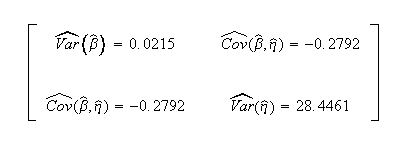

Weibull++ computed/variance covariance matrix:

The two-sided 95% bounds on the parameters can be determined from the QCP. Calculate and then click Report to see the results.

Interval Data MLE Example

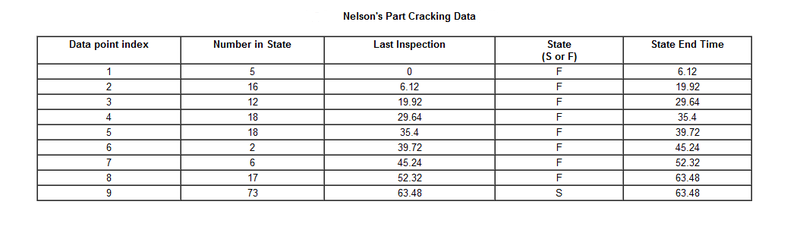

From Wayne Nelson, Applied Life Data Analysis, Page 415 [30]. 167 identical parts were inspected for cracks. The following is a table of their last inspection times and times-to-failure:

Published Results:

Published results (using MLE):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.486 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 71.687\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Published 95% FM confidence limits on the parameters:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=\lbrace 1.224, \text{ }1.802\rbrace \\ & \widehat{\eta} = \lbrace 61.962, \text{ }82.938\rbrace \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Published variance/covariance matrix:

Computed Results in Weibull++

This same data set can be entered into a Weibull++ standard folio that's configured for grouped times-to-failure data with suspensions and interval data.

Weibull++ computed parameters for maximum likelihood are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=1.485 \\ & \widehat{\eta} = 71.690\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Weibull++ computed 95% FM confidence limits on the parameters:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=\lbrace 1.224, \text{ }1.802\rbrace \\ & \widehat{\eta} = \lbrace 61.961, \text{ }82.947\rbrace \\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Weibull++ computed/variance covariance matrix:

Grouped Suspension MLE Example

From Dallas R. Wingo, IEEE Transactions on Reliability Vol. R-22, No 2, June 1973, Pages 96-100.

Wingo uses the following times-to-failure: 37, 55, 64, 72, 74, 87, 88, 89, 91, 92, 94, 95, 97, 98, 100, 101, 102, 102, 105, 105, 107, 113, 117, 120, 120, 120, 122, 124, 126, 130, 135, 138, 182. In addition, the following suspensions are used: 4 at 70, 5 at 80, 4 at 99, 3 at 121 and 1 at 150.

Published Results (using MLE)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=3.7596935\\ & \widehat{\eta} = 106.49758 \\ & \hat{\gamma }=14.451684\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Computed Results in Weibull++

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\beta }=3.7596935\\ & \widehat{\eta} = 106.49758 \\ & \hat{\gamma }=14.451684\\ \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Note that you must select the Use True 3-P MLEoption in the Weibull++ Application Setup to replicate these results.

3-P Probability Plot Example

Suppose we want to model a left censored, right censored, interval, and complete data set, consisting of 274 units under test of which 185 units fail. The following table contains the data.

| Data Point Index | Number in State | Last Inspection | State (S or F) | State End Time |

| 1 | 2 | 5 | F | 5 |

| 2 | 23 | 5 | S | 5 |

| 3 | 28 | 0 | F | 7 |

| 4 | 4 | 10 | F | 10 |

| 5 | 7 | 15 | F | 15 |

| 6 | 8 | 20 | F | 20 |

| 7 | 29 | 20 | S | 20 |

| 8 | 32 | 0 | F | 22 |

| 9 | 6 | 25 | F | 25 |

| 10 | 4 | 27 | F | 30 |

| 11 | 8 | 30 | F | 35 |

| 12 | 5 | 30 | F | 40 |

| 13 | 9 | 27 | F | 45 |

| 14 | 7 | 25 | F | 50 |

| 15 | 5 | 20 | F | 55 |

| 16 | 3 | 15 | F | 60 |

| 17 | 6 | 10 | F | 65 |

| 18 | 3 | 5 | F | 70 |

| 19 | 37 | 100 | S | 100 |

| 20 | 48 | 0 | F | 102 |

Solution

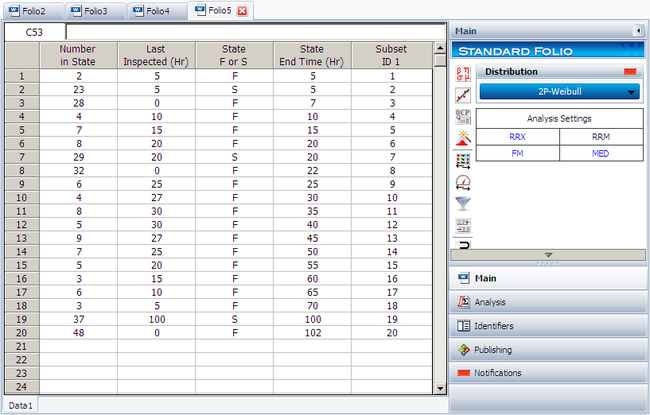

Since standard ranking methods for dealing with these different data types are inadequate, we will want to use the ReliaSoft ranking method. This option is the default in Weibull++ when dealing with interval data. The filled-out standard folio is shown next:

The computed parameters using MLE are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\beta }=0.748;\text{ }\hat{\eta }=44.38\,\! }[/math]

Using RRX:

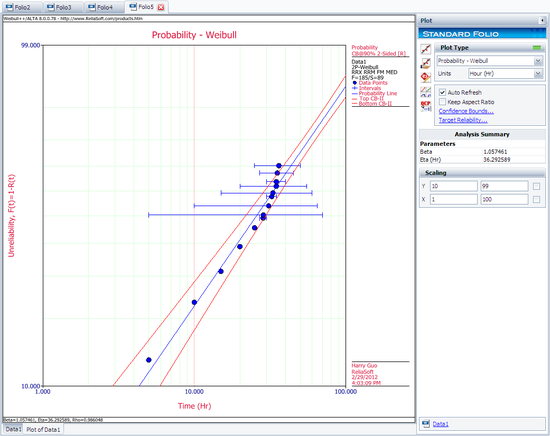

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\beta }=1.057;\text{ }\hat{\eta }=36.29\,\! }[/math]

Using RRY:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\beta }=0.998;\text{ }\hat{\eta }=37.16\,\! }[/math]

The plot with the two-sided 90% confidence bounds for the rank regression on X solution is:

The normal distribution, also known as the Gaussian distribution, is the most widely-used general purpose distribution. It is for this reason that it is included among the lifetime distributions commonly used for reliability and life data analysis. There are some who argue that the normal distribution is inappropriate for modeling lifetime data because the left-hand limit of the distribution extends to negative infinity. This could conceivably result in modeling negative times-to-failure. However, provided that the distribution in question has a relatively high mean and a relatively small standard deviation, the issue of negative failure times should not present itself as a problem. Nevertheless, the normal distribution has been shown to be useful for modeling the lifetimes of consumable items, such as printer toner cartridges.

Normal Probability Density Function

The pdf of the normal distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=\frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\frac{1}{2}{{\left( \frac{t-\mu }{\sigma } \right)}^{2}}}}\,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu\,\! }[/math] = mean of the normal times-to-faiure, also noted as [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{T}\,\! }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta\,\! }[/math] = standard deviation of the times-to-failure

It is a 2-parameter distribution with parameters [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \,\! }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{T}\,\! }[/math] ) and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }}\,\! }[/math] (i.e., the mean and the standard deviation, respectively).

Normal Statistical Properties

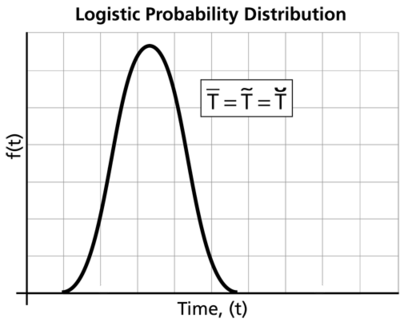

The Normal Mean, Median and Mode

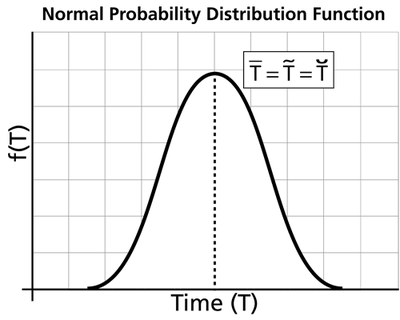

The normal mean or MTTF is actually one of the parameters of the distribution, usually denoted as [math]\displaystyle{ \mu .\,\! }[/math] Because the normal distribution is symmetrical, the median and the mode are always equal to the mean:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu =\tilde{T}=\breve{T}\,\! }[/math]

The Normal Standard Deviation

As with the mean, the standard deviation for the normal distribution is actually one of the parameters, usually denoted as [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }_{T}}\,\! }[/math].

The Normal Reliability Function

The reliability for a mission of time [math]\displaystyle{ T\,\! }[/math] for the normal distribution is determined by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)=\int_{t}^{\infty }f(x)dx=\int_{t}^{\infty }\frac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{x-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}dx\,\! }[/math]

There is no closed-form solution for the normal reliability function. Solutions can be obtained via the use of standard normal tables. Since the application automatically solves for the reliability, we will not discuss manual solution methods. For interested readers, full explanations can be found in the references.

The Normal Conditional Reliability Function

The normal conditional reliability function is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t|T)=\frac{R(T+t)}{R(T)}=\frac{\int_{T+t}^{\infty }\tfrac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{x-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}dx}{\int_{T}^{\infty }\tfrac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{x-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}dx}\,\! }[/math]

Once again, the use of standard normal tables for the calculation of the normal conditional reliability is necessary, as there is no closed form solution.

The Normal Reliable Life

Since there is no closed-form solution for the normal reliability function, there will also be no closed-form solution for the normal reliable life. To determine the normal reliable life, one must solve:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(T)=\int_{T}^{\infty }\frac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{t-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}dt\,\! }[/math]

for [math]\displaystyle{ T\,\! }[/math].

The Normal Failure Rate Function

The instantaneous normal failure rate is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda (t)=\frac{f(t)}{R(t)}=\frac{\tfrac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{t-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}}{\int_{t}^{\infty }\tfrac{1}{{{\sigma }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{x-\mu }{{{\sigma }}} \right)}^{2}}}}dx}\,\! }[/math]

Characteristics of the Normal Distribution

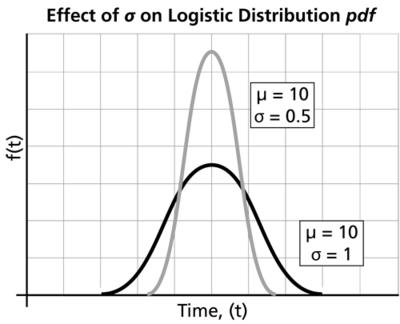

Some of the specific characteristics of the normal distribution are the following:

- The normal pdf has a mean, [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{T}\,\! }[/math], which is equal to the median, [math]\displaystyle{ \breve{T}\,\! }[/math], and also equal to the mode, [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{T}\,\! }[/math], or [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{T}=\breve{T}=\tilde{T}\,\! }[/math]. This is because the normal distribution is symmetrical about its mean.

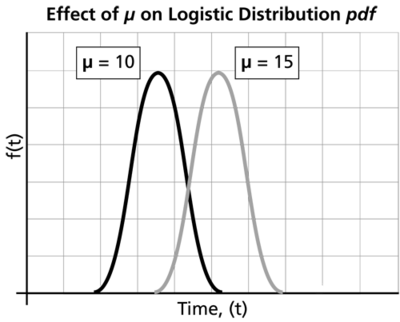

- The mean, [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \,\! }[/math], or the mean life or the [math]\displaystyle{ MTTF\,\! }[/math], is also the location parameter of the normal pdf, as it locates the pdf along the abscissa. It can assume values of [math]\displaystyle{ -\infty \lt \bar{T}\lt \infty \,\! }[/math].

- The normal pdf has no shape parameter. This means that the normal pdf has only one shape, the bell shape, and this shape does not change.

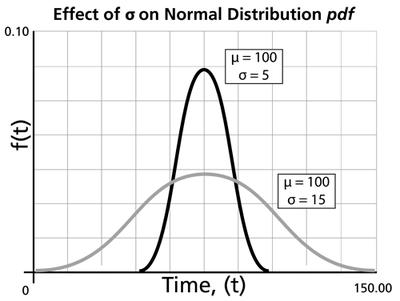

- The standard deviation, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }}\,\! }[/math], is the scale parameter of the normal pdf.

- As [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }}\,\! }[/math] decreases, the pdf gets pushed toward the mean, or it becomes narrower and taller.

- As [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }}\,\! }[/math] increases, the pdf spreads out away from the mean, or it becomes broader and shallower.

- The standard deviation can assume values of [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt {{\sigma }}\lt \infty \,\! }[/math].

- The greater the variability, the larger the value of [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }}\,\! }[/math], and vice versa.

- The standard deviation is also the distance between the mean and the point of inflection of the pdf, on each side of the mean. The point of inflection is that point of the pdf where the slope changes its value from a decreasing to an increasing one, or where the second derivative of the pdf has a value of zero.

- The normal pdf starts at [math]\displaystyle{ t=-\infty \,\! }[/math] with an [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=0\,\! }[/math]. As [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] increases, [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\,\! }[/math] also increases, goes through its point of inflection and reaches its maximum value at [math]\displaystyle{ t=\bar{T}\,\! }[/math]. Thereafter, [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\,\! }[/math] decreases, goes through its point of inflection, and assumes a value of [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)=0\,\! }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ t=+\infty \,\! }[/math].

Weibull++ Notes on Negative Time Values

One of the disadvantages of using the normal distribution for reliability calculations is the fact that the normal distribution starts at negative infinity. This can result in negative values for some of the results. Negative values for time are not accepted in most of the components of Weibull++, nor are they implemented. Certain components of the application reserve negative values for suspensions, or will not return negative results. For example, the Quick Calculation Pad will return a null value (zero) if the result is negative. Only the Free-Form (Probit) data sheet can accept negative values for the random variable (x-axis values).

Normal Distribution Examples

The following examples illustrate the different types of life data that can be analyzed in Weibull++ using the normal distribution. For more information on the different types of life data, see Life Data Classification.

Complete Data Example

6 units are tested to failure. The following failure times data are obtained: 12125, 11260, 12080, 12825, 13550 and 14670 hours. Assuming that the data are normally distributed, do the following:

Objectives

- 1. Find the parameters for the data set, using the Rank Regression on X (RRX) parameter estimation method

- 2. Obtain the probability plot for the data with 90%, two-sided Type 1 confidence bounds.

- 3. Obtain the pdf plot for the data.

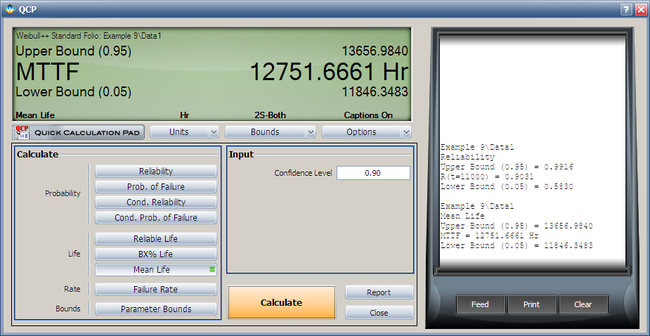

- 4. Using the Quick Calculation Pad (QCP), determine the reliability for a mission of 11,000 hours, as well as the upper and lower two-sided 90% confidence limit on this reliability.

- 5. Using the QCP, determine the MTTF, as well as the upper and lower two-sided 90% confidence limit on this MTTF.

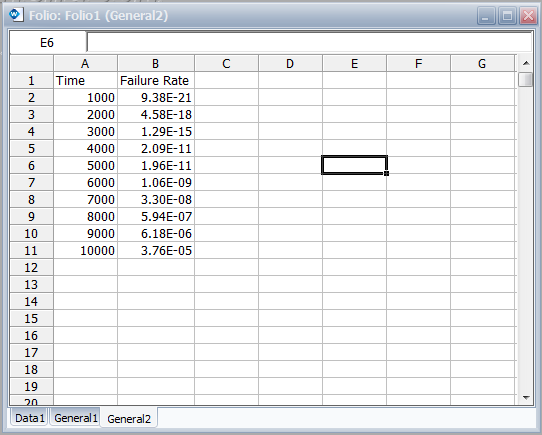

- 6. Obtain tabulated values for the failure rate for 10 different mission end times. The mission end times are 1,000 to 10,000 hours, using increments of 1,000 hours.

Solution

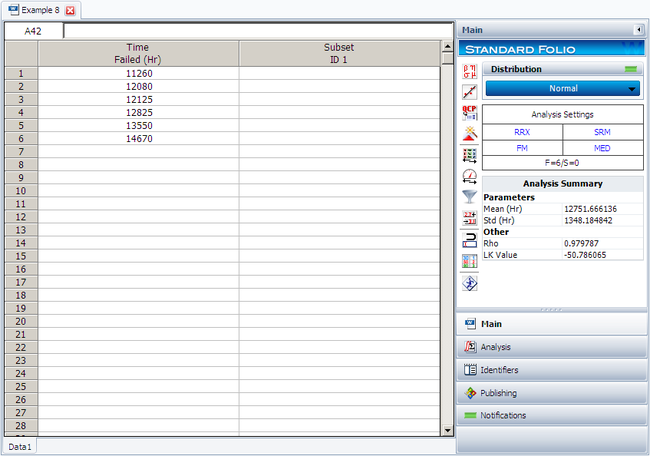

The following figure shows the data as entered in Weibull++, as well as the calculated parameters.

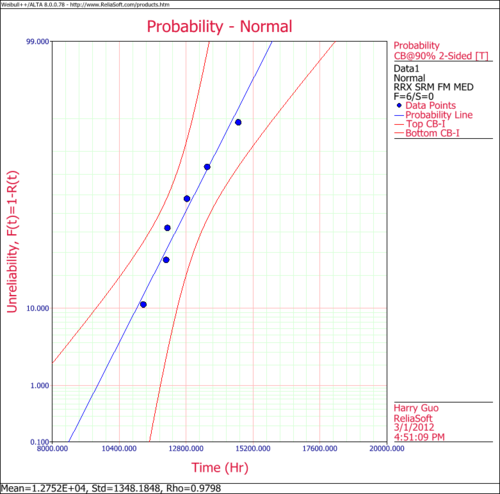

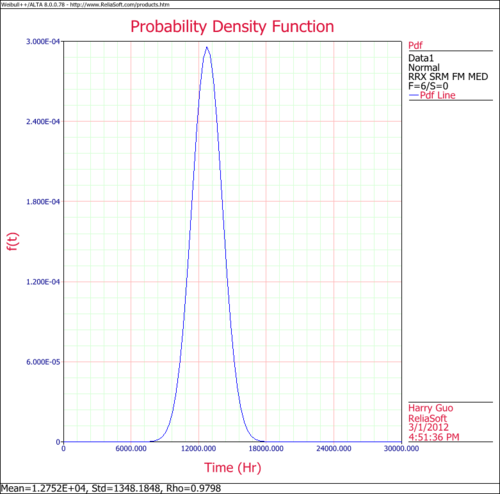

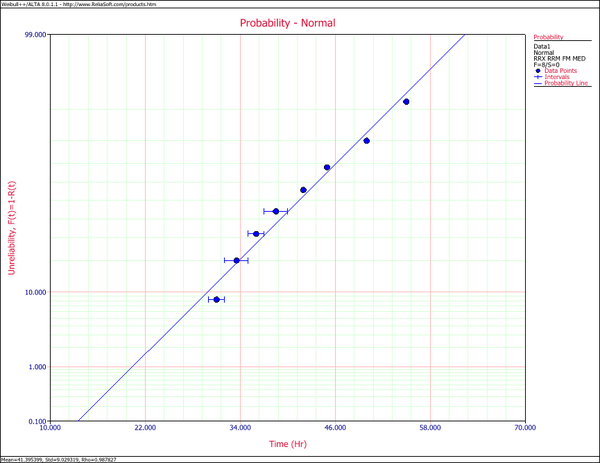

The following figures show the probability plot with the 90% two-sided confidence bounds and the pdf plot.

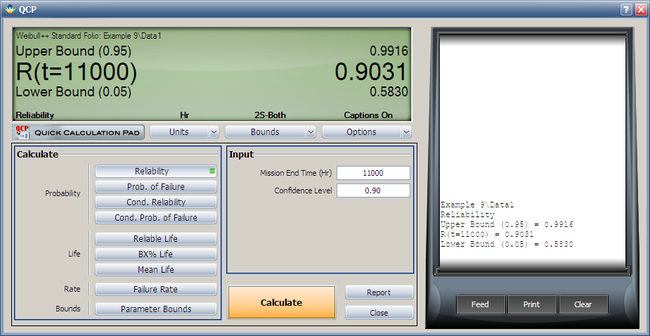

Both the reliability and MTTF can be easily obtained from the QCP. The QCP, with results, for both cases is shown in the next two figures.

To obtain tabulated values for the failure rate, use the Analysis Workbook or General Spreadsheet features that are included in Weibull++. (For more information on these features, please refer to the Weibull++ User's Guide. For a step-by-step example on creating Weibull++ reports, please see the Quick Start Guide). The following worksheet shows the mission times and the corresponding failure rates.

Suspension Data Example

19 units are being reliability tested and the following is a table of their times-to-failure and suspensions.

| Non-Grouped Data Times-to-Failure Data with Suspensions | ||

| Data point index | Last Inspected | State End Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 2 |

| 2 | S | 3 |

| 3 | F | 5 |

| 4 | S | 7 |

| 5 | F | 11 |

| 6 | S | 13 |

| 7 | S | 17 |

| 8 | S | 19 |

| 9 | F | 23 |

| 10 | F | 29 |

| 11 | S | 31 |

| 12 | F | 37 |

| 13 | S | 41 |

| 14 | F | 43 |

| 15 | S | 47 |

| 16 | S | 53 |

| 17 | F | 59 |

| 18 | S | 61 |

| 19 | S | 67 |

Using the normal distribution and the maximum likelihood (MLE) parameter estimation method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 48.07 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 28.41. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

If we analyze the data set with the rank regression on x (RRX) method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 46.40 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 28.64. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

For the rank regression on y (RRY) method, the parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 47.34 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 29.96. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Interval Censored Data Example

8 units are being reliability tested, and the following is a table of their failure times:

| Non-Grouped Interval Data | ||

| Data point index | Last Inspected | State End Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 32 |

| 2 | 32 | 35 |

| 3 | 35 | 37 |

| 4 | 37 | 40 |

| 5 | 42 | 42 |

| 6 | 45 | 45 |

| 7 | 50 | 50 |

| 8 | 55 | 55 |

This is a sequence of interval times-to-failure data. Using the normal distribution and the maximum likelihood (MLE) parameter estimation method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 41.40 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 7.740. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

For rank regression on x:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 41.40 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 9.03. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

If we analyze the data set with the rank regression on y (RRY) parameter estimation method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 41.39 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 9.25. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The following plot shows the results if the data were analyzed using the rank regression on X (RRX) method.

Mixed Data Types Example

Suppose our data set includes left and right censored, interval censored and complete data, as shown in the following table.

| Grouped Data Times-to-Failure with Suspensions and Intervals (Interval, Left and Right Censored) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data point index | Number in State | Last Inspection | State (S or F) | State End Time |

| 1 | 1 | 10 | F | 10 |

| 2 | 1 | 20 | S | 20 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | F | 30 |

| 4 | 2 | 40 | F | 40 |

| 5 | 1 | 50 | F | 50 |

| 6 | 1 | 60 | S | 60 |

| 7 | 1 | 70 | F | 70 |

| 8 | 2 | 20 | F | 80 |

| 9 | 1 | 10 | F | 85 |

| 10 | 1 | 100 | F | 100 |

Using the normal distribution and the maximum likelihood (MLE) parameter estimation method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 48.11 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 26.42 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

If we analyze the data set with the rank regression on x (RRX) method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 49.99 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 30.17 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

For the rank regression on y (RRY) method, the parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 51.61 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 33.07 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Comparison of Analysis Methods

8 units are being reliability tested, and the following is a table of their failure times:

| Non-Grouped Times-to-Failure Data | ||

| Data point index | State F or S | State End Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 2 |

| 2 | F | 5 |

| 3 | F | 11 |

| 4 | F | 23 |

| 5 | F | 29 |

| 6 | F | 37 |

| 7 | F | 43 |

| 8 | F | 59 |

Using the normal distribution and the maximum likelihood (MLE) parameter estimation method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 26.13 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 18.57 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

If we analyze the data set with the rank regression on x (RRX) method, the computed parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 26.13 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 21.64 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

For the rank regression on y (RRY) method, the parameters are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\mu }= & 26.13 \\ & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{T}}= & 22.28. \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

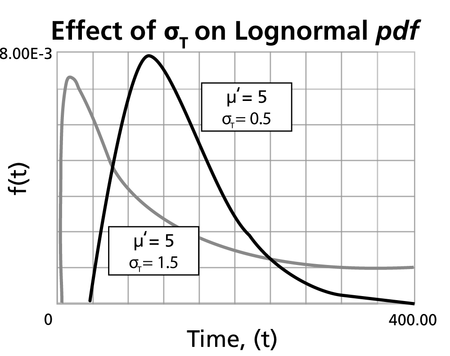

The lognormal distribution is commonly used to model the lives of units whose failure modes are of a fatigue-stress nature. Since this includes most, if not all, mechanical systems, the lognormal distribution can have widespread application. Consequently, the lognormal distribution is a good companion to the Weibull distribution when attempting to model these types of units.

As may be surmised by the name, the lognormal distribution has certain similarities to the normal distribution. A random variable is lognormally distributed if the logarithm of the random variable is normally distributed. Because of this, there are many mathematical similarities between the two distributions. For example, the mathematical reasoning for the construction of the probability plotting scales and the bias of parameter estimators is very similar for these two distributions.

Lognormal Probability Density Function

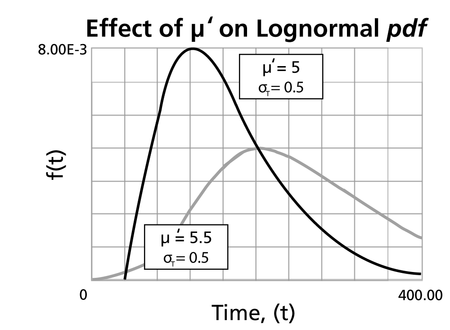

The lognormal distribution is a 2-parameter distribution with parameters [math]\displaystyle{ {\mu }'\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma'\,\! }[/math]. The pdf for this distribution is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f({t}')=\frac{1}{{{\sigma' }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{{{t}^{\prime }}-{\mu }'}{{{\sigma' }}} \right)}^{2}}}}\,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {t}'=\ln (t)\,\! }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] values are the times-to-failure

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu'\,\! }[/math] = mean of the natural logarithms of the times-to-failure

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma'\,\! }[/math] = standard deviation of the natural logarithms of the times-to-failure

The lognormal pdf can be obtained, realizing that for equal probabilities under the normal and lognormal pdfs, incremental areas should also be equal, or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} f(t)dt=f({t}')d{t}' \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Taking the derivative of the relationship between [math]\displaystyle{ {t}'\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {t}\,\! }[/math] yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ d{t}'=\frac{dt}{t}\,\! }[/math]

Substitution yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} f(t)= & \frac{f({t}')}{t} \\ f(t)= & \frac{1}{t\cdot {{\sigma' }}\sqrt{2\pi }}{{e}^{-\tfrac{1}{2}{{\left( \tfrac{\text{ln}(t)-{\mu }'}{{{\sigma' }}} \right)}^{2}}}} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(t)\ge 0,t\gt 0,-\infty \lt {\mu }'\lt \infty ,{{\sigma' }}\gt 0\,\! }[/math]

Lognormal Distribution Functions

The Mean or MTTF

The mean of the lognormal distribution, [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \,\! }[/math], is discussed in Kececioglu [19]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu ={{e}^{{\mu }'+\tfrac{1}{2}\sigma'^{2}}}\,\! }[/math]