Template:Fleet analysis rsa: Difference between revisions

(Created page with '==Fleet Analysis== <br> Fleet analysis is similar to the repairable systems analysis described previously. The main difference is that a fleet of systems is considered and the mo…') |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

{{methodology fleet rsa}} | |||

{ | |||

===Data Analysis=== | ===Data Analysis=== | ||

Revision as of 22:57, 10 January 2012

Fleet Analysis

Fleet analysis is similar to the repairable systems analysis described previously. The main difference is that a fleet of systems is considered and the models are applied to the fleet failures rather than to the system failures. In other words, repairable system analysis models the number of system failures versus system time; whereas fleet analysis models the number of fleet failures versus fleet time.

The main motivation for fleet analysis is to enable the application of the Crow Extended model for fielded data. In many cases, reliability improvements might be necessary on systems that are already in the field. These types of reliability improvements are essentially delayed fixes (BD modes) as described in Chapter 9.

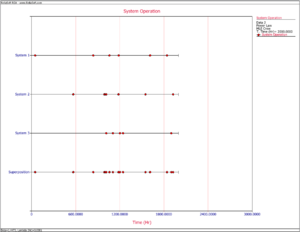

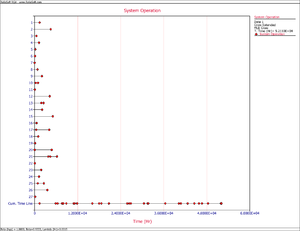

Recall from Chapter 9 that in order to make projections using the Crow Extended model, the [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] of the combined A and BD modes should be equal to 1. Since the failure intensity in a fielded system might be changing over time (e.g. increasing if the system wears out), this assumption might be violated. In such a scenario, the Crow Extended model cannot be used. However, if a fleet of systems is considered and the number of fleet failures versus fleet time is modeled, the failures might become random. This is because there is a mixture of systems within a fleet, new and old, and when the failures of this mixture of systems are viewed from a cumulative fleet time point of view, they may be random. Figures Repairable and Fleet illustrate this concept. Figure Repairable shows the number of failures over system age. It can be clearly seen that as the systems age, the intensity of the failures increases (wearout). The superposition system line, which brings the failures from the different systems under a single timeline, also illustrates this observation. On the other hand, if you take the same four systems and combine their failures from a fleet perspective, and consider fleet failures over cumulative fleet hours, then the failures seem to be random. Figure Fleet illustrates this concept in the System Operation plot when you consider the Cum. Time Line. In this case, the [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] of the fleet will be equal to 1 and the Crow Extended model can be used for quantifying the effects of future reliability improvements on the fleet.

Methodology

Figures Repairable and Fleet illustrate that the difference between repairable system data analysis and fleet analysis is the way that the dataset is treated. In fleet analysis, the time-to-failure data from each system is stacked to a cumulative timeline. For example, consider the two systems in Table 13.2.

| Table 13.2 - System data | ||

| System | Failure Times (hr) | End Time (hr) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3, 7 | 10 |

| 2 | 4, 9, 13 | 15 |

The data set is first converted to an accumulated timeline, as follows:

- • System 1 is considered first. The accumulated timeline is therefore 3 and 7 hours.

- • System 1's End Time is 10 hours. System 2's first failure is at 4 hours. This failure time is added to System 1's End Time to give an accumulated failure time of 14 hours.

- • The second failure for System 2 occurred 5 hours after the first failure. This time interval is added to the accumulated timeline to give 19 hours.

- • The third failure for System 2 occurred 4 hours after the second failure. The accumulated failure time is 19 + 4 = 23 hours.

- • System 2's end time is 15 hours, or 2 hours after the last failure. The total accumulated operating time for the fleet is 25 hours (23 + 2 = 25).

In general, the accumulated operating time [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{j}} }[/math] is calculated by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{j}}={{X}_{i,q}}+\underset{q=1}{\overset{K-1}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{T}_{q}},\text{ }m=1,2,...,N }[/math]

- where:

- • [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{i,q}} }[/math] is the [math]\displaystyle{ {{i}^{th}} }[/math] failure of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{q}^{th}} }[/math] system

- • [math]\displaystyle{ {{T}_{q}} }[/math] is the end time of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{q}^{th}} }[/math] system

- • [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is the total number of systems

- • [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is the total number of failures from all systems ( [math]\displaystyle{ N=\underset{j=1}{\overset{K}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{N}_{q}} }[/math] )

As this example demonstrates, the accumulated timeline is determined based on the order of the systems. So if you consider the data in Table 13.2 by taking System 2 first, the accumulated timeline would be: 4, 9, 13, 18, 22, with an end time of 25. Therefore, the order in which the systems are considered is somewhat important. However, in the next step of the analysis the data from the accumulated timeline will be grouped into time intervals, effectively eliminating the importance of the order of the systems. Keep in mind that this will NOT always be true. This is true only when the order of the systems was random to begin with. If there is some logic/pattern in the order of the systems, then it will remain even if the cumulative timeline is converted to grouped data. For example, consider a system that wears out with age. This means that more failures will be observed as this system ages and these failures will occur more frequently. Within a fleet of such systems, there will be new and old systems in operation. If the dataset collected is considered from the newest to the oldest system, then even if the data points are grouped, the pattern of fewer failures at the beginning and more failures at later time intervals will still be present. If the objective of the analysis is to determine the difference between newer and older systems, then that order for the data will be acceptable. However, if the objective of the analysis is to determine the reliability of the fleet, then the systems should be randomly ordered.

Data Analysis

Once the accumulated timeline has been generated, it is then converted into grouped data. To accomplish this, a group interval is required. The group interval length should be chosen so that it is representative of the data. Also note that the intervals do not have to be of equal length. Once the data points have been grouped, the parameters can be obtained using maximum likelihood estimation as described in Chapter 5 in the Grouped Data Analysis section. The data in Table 13.2 can be grouped into 5 hr intervals. This interval length is sufficiently large to insure that there are failures within each interval. The grouped data set is given in Table 13.3.

| Table 13.3 - Grouped data | |

| Failures in Interval | Interval End Time |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

| 1 | 10 |

| 1 | 15 |

| 1 | 20 |

| 1 | 25 |

The Crow-AMSAA model for Grouped Failure Times is used for the data in Table 13.3 and the parameters of the model are solved by satisfying the following maximum likelihood equations (Chapter 5).

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{matrix} \widehat{\lambda }=\frac{n}{T_{k}^{\widehat{\beta }}} \\ \underset{i=1}{\overset{k}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{n}_{i}}\left[ \frac{T_{i}^{\widehat{\beta }}\ln {{T}_{i-1}}-T_{i-1}^{\widehat{\beta }}\ln {{T}_{i-1}}}{T_{i}^{\widehat{\beta }}-T_{i-1}^{\widehat{\beta }}}-\ln {{T}_{k}} \right]=0 \\ \end{matrix} }[/math]

Example 4

Table 13.4 presents data for a fleet of 27 systems. A cycle is a complete history from overhaul to overhaul. The failure history for the last completed cycle for each system is recorded. This is a random sample of data from the fleet. These systems are in the order in which they were selected. Suppose the intervals to group the current data are 10000, 20000, 30000, 40000 and the final interval is defined by the termination time. Conduct the fleet analysis.

| Table 13.4 - Sample fleet data | |||

| System | Cycle Time [math]\displaystyle{ {{T}_{j}} }[/math] | Number of failures [math]\displaystyle{ {{N}_{j}} }[/math] | Failure Time [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{ij}} }[/math] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1396 | 1 | 1396 |

| 2 | 4497 | 1 | 4497 |

| 3 | 525 | 1 | 525 |

| 4 | 1232 | 1 | 1232 |

| 5 | 227 | 1 | 227 |

| 6 | 135 | 1 | 135 |

| 7 | 19 | 1 | 19 |

| 8 | 812 | 1 | 812 |

| 9 | 2024 | 1 | 2024 |

| 10 | 943 | 2 | 316, 943 |

| 11 | 60 | 1 | 60 |

| 12 | 4234 | 2 | 4233, 4234 |

| 13 | 2527 | 2 | 1877, 2527 |

| 14 | 2105 | 2 | 2074, 2105 |

| 15 | 5079 | 1 | 5079 |

| 16 | 577 | 2 | 546, 577 |

| 17 | 4085 | 2 | 453, 4085 |

| 18 | 1023 | 1 | 1023 |

| 19 | 161 | 1 | 161 |

| 20 | 4767 | 2 | 36, 4767 |

| 21 | 6228 | 3 | 3795, 4375, 6228 |

| 22 | 68 | 1 | 68 |

| 23 | 1830 | 1 | 1830 |

| 24 | 1241 | 1 | 1241 |

| 25 | 2573 | 2 | 871, 2573 |

| 26 | 3556 | 1 | 3556 |

| 27 | 186 | 1 | 186 |

| Total | 52110 | 37 | |

Solution

For the system data in Table 13.4, the data can be grouped into 10000, 20000, 30000, 4000 and 52110 time intervals. Table 13.5 gives the grouped data.

| Table 13.5 - Grouped data | |

| Time | Observed Failures |

|---|---|

| 10000 | 8 |

| 20000 | 16 |

| 30000 | 22 |

| 40000 | 27 |

| 52110 | 37 |

Based on the above time intervals, the maximum likelihood estimates of [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{\lambda } }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{\beta } }[/math] for this data set are then given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{matrix} \widehat{\lambda }=0.00147 \\ \widehat{\beta }=0.93328 \\ \end{matrix} }[/math]

Figure fle shows the System Operation plot.

[math]\displaystyle{ }[/math]

Applying the Crow Extended Model to Fleet Data

As it was mentioned previously, the main motivation of the fleet analysis is to apply the Crow Extended model for in-service reliability improvements. The methodology to be used is identical to the application of the Crow Extended model for Grouped Data described in Chapter 9. Consider the fleet data in Table 13.4. In order to apply the Crow Extended model, put [math]\displaystyle{ N=37 }[/math] failure times on a cumulative time scale over [math]\displaystyle{ (0,T) }[/math] , where [math]\displaystyle{ T=52110 }[/math] . In the example, each [math]\displaystyle{ {{T}_{i}} }[/math] corresponds to a failure time [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{ij}} }[/math] . This is often not the situation. However, in all cases the accumulated operating time [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{q}} }[/math] at a failure time [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{ir}} }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & {{Y}_{q}}= & {{X}_{i,r}}+\underset{j=1}{\overset{r-1}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{T}_{j}},\ \ \ q=1,2,\ldots ,N \\ & N= & \underset{j=1}{\overset{K}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{N}_{j}} \end{align} }[/math]

And [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] indexes the successive order of the failures. Thus, in this example [math]\displaystyle{ N=37,\,{{Y}_{1}}=1396,\,{{Y}_{2}}=5893,\,{{Y}_{3}}=6418,\ldots ,{{Y}_{37}}=52110 }[/math] . See Table 13.6.

| Table 13.6 - Test-find-test fleet data | ||||||

| [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{q}} }[/math] | Mode | [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{q}} }[/math] | Mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1396 | BD1 | 20 | 26361 | BD1 | |

| 2 | 5893 | BD2 | 21 | 26392 | A | |

| 3 | 6418 | A | 22 | 26845 | BD8 | |

| 4 | 7650 | BD3 | 23 | 30477 | BD1 | |

| 5 | 7877 | BD4 | 24 | 31500 | A | |

| 6 | 8012 | BD2 | 25 | 31661 | BD3 | |

| 7 | 8031 | BD2 | 26 | 31697 | BD2 | |

| 8 | 8843 | BD1 | 27 | 36428 | BD1 | |

| 9 | 10867 | BD1 | 28 | 40223 | BD1 | |

| 10 | 11183 | BD5 | 29 | 40803 | BD9 | |

| 11 | 11810 | A | 30 | 42656 | BD1 | |

| 12 | 11870 | BD1 | 31 | 42724 | BD10 | |

| 13 | 16139 | BD2 | 32 | 44554 | BD1 | |

| 14 | 16104 | BD6 | 33 | 45795 | BD11 | |

| 15 | 18178 | BD7 | 34 | 46666 | BD12 | |

| 16 | 18677 | BD2 | 35 | 48368 | BD1 | |

| 17 | 20751 | BD4 | 36 | 51924 | BD13 | |

| 18 | 20772 | BD2 | 37 | 52110 | BD2 | |

| 19 | 25815 | BD1 | ||||

Each system failure time in Table 13.4 corresponds to a problem and a cause (failure mode). The management strategy can be to not fix the failure mode (A mode) or to fix the failure mode with a delayed corrective action (BD mode). There are [math]\displaystyle{ {{N}_{A}}=4 }[/math] failures due to A failure modes. There are [math]\displaystyle{ {{N}_{BD}}=33 }[/math] total failures due to [math]\displaystyle{ M=13 }[/math] distinct BD failure modes. Some of the distinct BD modes had repeats of the same problem. For example, mode BD1 had 12 occurrences of the same problem. Therefore, in this example, there are 13 distinct corrective actions corresponding to 13 distinct BD failure modes. The objective of the Crow Extended model is to estimate the impact of the 13 distinct corrective actions.The analyst will choose an average effectiveness factor (EF) based on the proposed corrective actions and historical experience. Historical industry and government data supports a typical average effectiveness factor [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{d}=.70 }[/math] for many systems. In this example, an average EF of [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{d}=0.4 }[/math] was assumed in order to be conservative regarding the impact of the proposed corrective actions. Since there are no BC failure modes (corrective actions applied during the test), the projected failure intensity is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{r}(T)=\left( \frac{{{N}_{A}}}{T}+\underset{i=1}{\overset{M}{\mathop \sum }}\,(1-{{d}_{i}})\frac{{{N}_{i}}}{T} \right)+\overline{d}h(T) }[/math]

The first term is estimated by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\widehat{\lambda }}_{A}}=\frac{{{N}_{A}}}{T}=0.000077 }[/math]

The second term is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{i=1}{\overset{M}{\mathop \sum }}\,(1-{{d}_{i}})\frac{{{N}_{i}}}{T}=0.00038 }[/math]

This estimates the growth potential failure intensity:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & {{\widehat{\gamma }}_{GP}}(T)= & \frac{{{N}_{A}}}{T}+\underset{i=1}{\overset{M}{\mathop \sum }}\,(1-{{d}_{i}})\frac{{{N}_{i}}}{T} \\ & = & 0.00046 \end{align} }[/math]

To estimate the last term [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{d}h(T) }[/math] of the Crow Extended model, partition the data in Table 13.6 into intervals. This partition consists of [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] successive intervals. The length of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{q}^{th}} }[/math] interval is [math]\displaystyle{ {{L}_{q}}, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \,q=1,2,\ldots ,D }[/math] . It is not required that the intervals be of the same length, but there should be several (e.g. at least 5) cycles per interval on average. Also, let [math]\displaystyle{ {{S}_{1}}={{L}_{1}}, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ {{S}_{2}}={{L}_{1}}+{{L}_{2}},\ldots , }[/math] etc. be the accumulated time through the [math]\displaystyle{ {{q}^{th}} }[/math] interval. For the [math]\displaystyle{ {{q}^{th}} }[/math] interval note the number of distinct BD modes, [math]\displaystyle{ M{{I}_{q}} }[/math] , appearing for the first time, [math]\displaystyle{ q=1,2,\ldots ,D }[/math] . See Table 13.7.

| Table 13.7 - Grouped data for distinct BD modes | |||

| Interval | No. of Distinct BD Mode Failures | Length | Accumulated Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MI [math]\displaystyle{ _{1} }[/math] | L [math]\displaystyle{ _{1} }[/math] | S [math]\displaystyle{ _{1} }[/math] |

| 2 | MI [math]\displaystyle{ _{2} }[/math] | L [math]\displaystyle{ _{2} }[/math] | S [math]\displaystyle{ _{2} }[/math] |

| . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . |

| D | MI [math]\displaystyle{ _{D} }[/math] | L [math]\displaystyle{ _{D} }[/math] | S [math]\displaystyle{ _{D} }[/math] |

The term [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{h}(T) }[/math] is calculated as [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{h}(T)=\widehat{\lambda }\widehat{\beta }{{T}^{\widehat{\beta }-1}} }[/math] and the values [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{\lambda } }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{\beta } }[/math] satisfy Eqns. (cc1) and (cc2). This is the grouped data version of the Crow-AMSAA model applied only to the first occurrence of distinct BD modes.

For the data in Table 13.6 the first 4 intervals had a length of 10000 and the last interval was 12110. Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ D=5 }[/math] . This choice gives an average of about 5 overhaul cycles per interval. See Table 13.8.

| Table 13.8 - Grouped data for distinct BD modes from Table 13.6 | |||

| Interval | No. of Distinct BD Mode Failures | Length | Accumulated Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 10000 | 10000 |

| 2 | 3 | 10000 | 20000 |

| 3 | 1 | 10000 | 30000 |

| 4 | 0 | 10000 | 40000 |

| 5 | 5 | 12110 | 52110 |

| Total | 13 | ||

- Thus:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{\lambda }= & 0.00330 \\ & \widehat{\beta }= & 0.76219 \end{align} }[/math]

- This gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{h}(T)= & \widehat{\lambda }\widehat{\beta }{{T}^{\widehat{\beta }-1}} \\ & = & 0.00019 \end{align} }[/math]

Consequently, for [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{d}=0.4 }[/math] the last term of the Crow Extended model is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{d}h(T)=0.000076 }[/math]

The projected failure intensity is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \widehat{r}(T)= & \frac{{{N}_{A}}}{T}+\underset{i=1}{\overset{M}{\mathop \sum }}\,(1-{{d}_{i}})\frac{{{N}_{i}}}{T}+\overline{d}h(T) \\ & = & 0.000077+0.6\times (0.00063)+0.4\times (0.00019) \\ & = & 0.000533 \end{align} }[/math]

This estimates that the 13 proposed corrective actions will reduce the number of failures per cycle of operation hours from the current [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{r}(0)=\tfrac{{{N}_{A}}+{{N}_{BD}}}{T}=0.00071 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat{r}(T)=0.00053. }[/math] The average time between failures is estimated to increase from the current 1408.38 hours to 1876.93 hours.

Confidence Bounds

For fleet data analysis using the Crow-AMSAA model, the confidence bounds are calculated using the same procedure as described in Section 5.4. For fleet data analysis using the Crow Extended model, the confidence bounds are calculated using the same procedure as described in Section 9.6.1.